If you’re anything like us, you’ll know that plant friends are temporary. Sometimes all of your love, stress, and waking attention is just not enough to keep them happy or even alive.

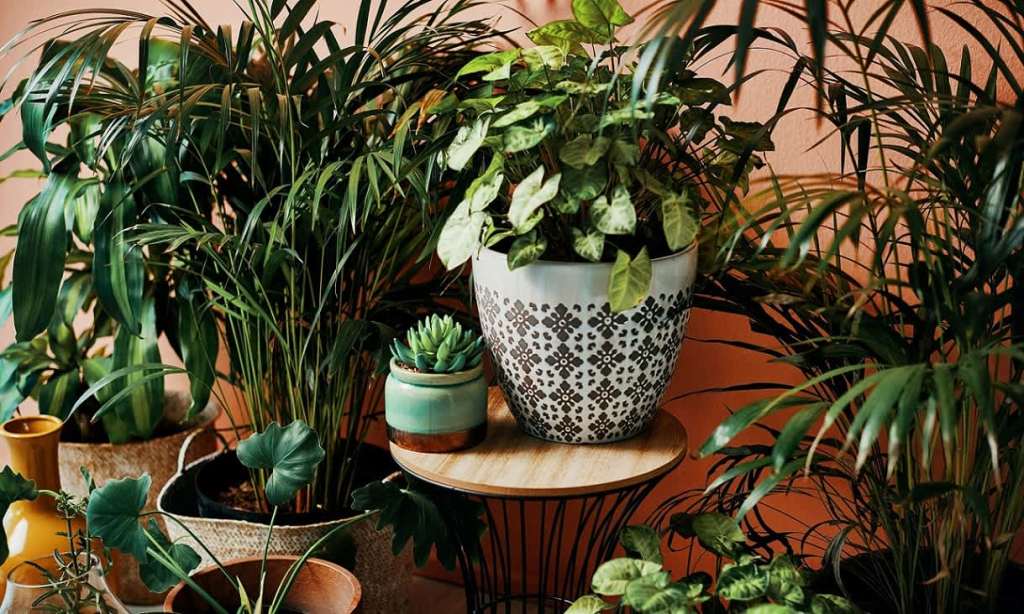

Last year, Aussies collectively spent $2.6 billion dollars on plants, buying some two billion green friends to keep us company during lockdown. Soaring plant sales were largely down to the growing trends of herb gardening and the ‘Plantstagram’ section of social media displaying lush indoor jungles.

Overall, we spent more $200 million more on plants in 2019/2020 than the previous financial year.

While it’s been an obvious boon for Australia’s horticulture industry, which employs more than 23,000 people across more than 1,600 businesses, it hasn’t been great for our native flora and fauna.

We all now know that keeping an indoor jungle thriving is tough work. If you’re staring down a few green remnants in an otherwise barren and brown plant pot, here’s why you shouldn’t just chuck that deceased decor outside.

Little shop of horrors

Australia hasn’t got a great history of bringing invasive foreign species into our fragile ecosystem. From rabbits, to foxes, to politicians, we introduce things into this country with little regard or understanding of the consequences.

Some 27,000 species of plants have been introduced and experts say they now outweigh the number of native plant species in the country. Around 10 per cent of these have become ‘naturalised’ or ‘established’, meaning that they thrive by themselves in the wild.

Almost all of the house plants sold in big plant stores that also sell hardware (not naming any names), and the smaller, Insta-friendly boutique shops are foreign imports.

They’re chosen because of their striking colouring, interesting leaves, and typically because they grow well indoors with little care or attention. That also makes them great escape artists, just ready to let loose on the garden or the neighbourhood.

John De Jose, CEO of the environmental organisation, Invasive Species Council, has said that each introduced species needs to be considered potentially dangerous for our biodiversity.

“The majority of introduced plants which have already become established in the wild are causing harm and are regarded as invasive”, he says.

“Some of the seemingly harmless introduced plants of today may very well turn out to be the devastating weeds of tomorrow.”

It’s hard to know whether an introduced houseplant will thrive in Australia because the conditions largely dictate their success. Some plants may lie dormant or relatively benign until they become problematic.

A long-lived tree might not become an issue until several hundred years after introduction.

Although Australia has some of the toughest biosecurity laws on the planet, plants that are already here can easily grow unchecked and smother the natives without us realising. That has serious knock on effects for the local wildlife and the ecosystem as a whole.

Even if you’ve got what you’re sure is a dead plant, it’s always best to put it in the green waste where it will be disposed of properly.

Houseplants are sold as being ‘unkillable’ for a reason and even if you have managed the reportedly impossible, there’s every chance they can do a Day of The Dead if the conditions are right.

Monstera madness

The Monstera deliciosa, arguably the most iconic house plant of all time, is notable for its rapid growth and ability to withstand even the toughest love from its parents.

The plant’s quick transformation from a three-leaved cutie to a towering jungle plant is what attracts buyers but it also makes it a great one for exploring the outdoors unaccompanied.

Monsteras are native to Central and South America but have become invasive in places like Hawaii where they thrive on the humidity.

Monsteras are regarded as environmental weeds in New South Wales where they are commonly found in urban bushland areas, usually in places where garden waste has been dumped.

It was first recorded as a naturalised plant in New South Wales in 2003, but had probably been naturalised for some time. It was also recently recorded as naturalised in Queensland where it grows freely in suburban coastal bushland, again, near garden waste sites.

Sneaky spider plants

Spider plants are easy to maintain and look after and they reproduce asexually through throwing out little spider plant pups that look great and provide their owners endless free plant babies.

This skill, of course, makes them dangerous fugitives and they are regarded as a minor environmental weed in New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria where they are often introduced accidentally.

Once established, the plantlets spread out from the mother plant, rapidly forming dense clusters of vegetation that strangle native competitors.

They’re not particularly picky about where they live either and have been found spreading into sandstone cracks and recently burnt bushland.

Pothos panic

Pothos or Devil’s Ivy is so hardy that they’ve been known to be able to grow indoors without any natural light, surviving off of the glow of lightbulbs alone.

While they’re great for any black thumbs that can’t get anything else to survive in their life-less abode, they’re also highly problematic for our native wildlife.

Pothos are highly toxic and they are illegal to grow in several US states because of this as well as their rapid growth. They seem to follow people everywhere, to the point that it’s actually difficult to identify their native origins.

They also grow to massive sizes, with leaves up to several feet in length when given the right conditions. They’re considered an invasive species and are a particular problem in Australia’s tropical north where they grow rampantly.

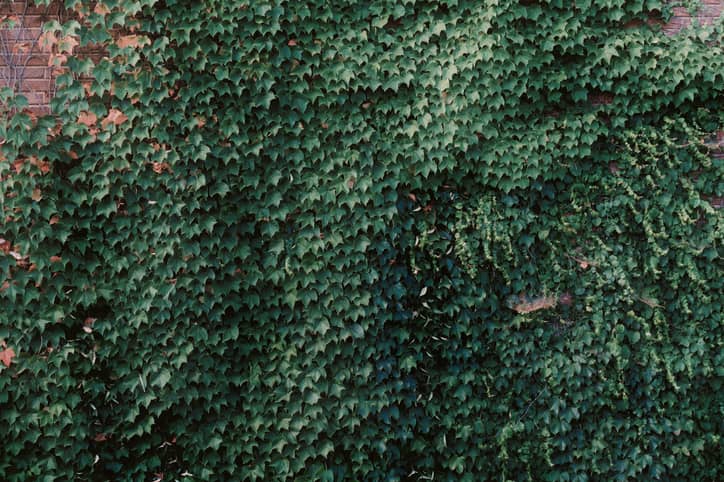

Invasive ivy

English Ivy looks great and does well indoors. The difficulty is that it also does well everywhere else.

English Ivy is considered a “significant environmental weed” in Victoria, the ACT, South Australia, New South Wales and Tasmania. It’s a species of top concern for natural resource management groups and is actively destroyed by community groups in Victoria and Tasmania.

They are extremely tolerant of conditions where natives usually aren’t, thriving in deep shade and with a canny ability to rapidly ascend walls and fences.

They blanket the ground in a thick mat of vegetation, excluding light from other species and are a direct threat to the survival of the superb lyrebird in the Dandenong Ranges.

If you have any of these, don’t panic. Just make sure to keep a good eye on them in case they look like they might be about to make a break for it.

This is likely not the case for most of us, whose plants couldn’t even outgrow their pots, let alone the garden.

Still, if you think they’re dead, just make sure to dispose of them responsibly.

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.