Australia’s very first International Women’s Day was held in 1928 in Sydney. There, the Militant Women’s Movement called for equal pay for equal work, an eight-hour working day for shop girls, and paid leave.

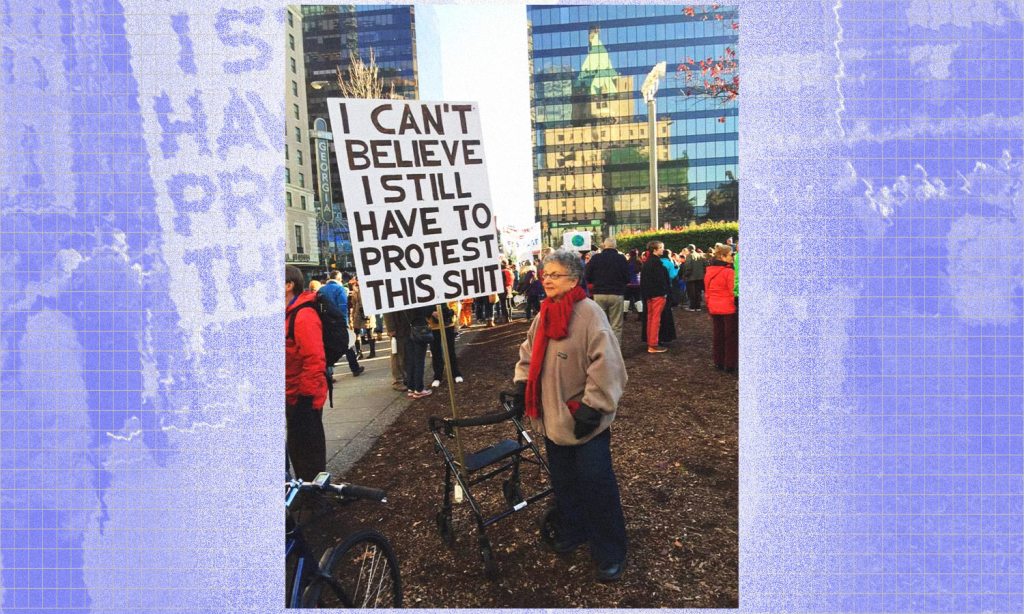

Nearly a century later and those demands don’t seem so radical, nor do they seem so unfamiliar. Women in 2023 are still calling for equal pay, fair working conditions, and paid maternity, menstrual, and miscarriage leave.

While it’s a day to celebrate the achievements of women in this country, IWD has its roots in protest, something that many feel has been lost in the corporatisation of the day. Instead of revolution, women are given cupcakes and breakfast panels on ‘leaning in’. Specific actions and specific changes are rarely spoken about. You’re more likely to see a corporation say, generally and blandly, that they ‘support women’ than you are to see one say ‘we’ve actively addressed the gender balance at our C-suite level’.

This is a shame because feminism, the philosophical belief that men and women should have equal rights and opportunities, is something we still very much need in this country. While IWD is a gentle reminder of that, in recent years it has been critiqued for not going far enough, falling into the banal box-checking exercise that so many diversity and progressive movements often do.

Here’s how far we’ve come and where we still need to go.

A Very Brief History of Women’s Rights in Australia

Indigenous Gender Relations

It’s a sad fact that much of so-called Australia’s social history was destroyed in the invasion and colonisation of this land by British forces. We have a remarkably limited understanding of what gender relations were like in Indigenous societies for the 60,000 or so years prior to 1776. However, the concept of ‘gender equality’ is entirely a European one, and perhaps not something that needed to be imported.

European anthropologists have historically considered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to have been subservient to men, but this is likely not the case. Early colonial accounts of Indigenous gender relations were coloured not only by the lens of European standards and expectations but by witnessing societies under attack.

The roles of men and women in many Indigenous cultures were prescribed by a religious philosophy that ensured balance and cooperation. Women played equally important roles in community survival as men did, with economic and political power over areas of society drawn from their gender and their ability to create life. They did, and continue to, perform specific dances and ceremonies and were the primary providers of food in their communities. It is however thought that women often did not have much choice when it came to marriage and partners.

Post-Colonial Women

When European colonisation began in 1788, British gender philosophy was largely imported. Women were broadly reliant on men for economic support, with many female convicts forced into prostitution and domestic servitude. Women had very few legal rights to property, wages, divorce, or even their own children.

The situation did not change much until the late 1800s, when the women’s suffrage movement began to take hold. Women were constantly agitating for political change as the rights to education expanded and, in 1861, land-owning women were given the right to vote in local elections in South Australia.

Womens Suffrage

The first women’s trade union, the Tailoresses Association of Melbourne, was established in 1882 and, two years later, the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society was formed. These women lobbied the government, held public debates, and went door-to-door throughout the colonies petitioning for equal rights.

South Australia again led the way in granting all women the right to vote and stand for election in 1894. When Australia was federated, in 1901, women could not vote, but this changed just one year later, giving women the right to run for office and vote in the first federal election in 1903 — Aboriginal women were however denied this right until 1962. But the women’s movement did not stop there, with protests, rallies, and even bombings used to agitate for equality in work, marriage, and for reproductive rights, as well as the rights of Indigenous women.

Feminism Takes Hold in the 20th Century

During the First World War, as in Europe, women began to enter typically male spaces like factories and mills as the men went off to fight. Their movements in these areas were often criticised but they worked hard to support the war efforts through charity and nursing organisations.

Edith Cowan, the woman on the back of the $50 note, became the first woman to take office in Parliament in 1920 in Western Australia and, in 1943, Enid Lyons and Dorothy Tangney became our first female federal Parliamentarians. 1922 also saw the foundation of the Country Women’s Association, still one of the largest female-led political organisations in Australia, that championed charitable causes and gave women spaces to socialise.

In 1933 we got the first women’s magazine, Women’s Weekly, although it wasn’t edited by a woman until Ita Buttrose took over in 1975.

World War II had a similar impact on women’s roles as the First World War as Australian men realised it didn’t make a lot of economic sense to repress half the population. Women flooded into the workforce in unprecedented numbers, helped by the Australian Womens Land Army and the Australian Women’s Army Service. Thousands of Australian female nurses also served overseas.

Second Wave Feminism

While the first wave of feminism focused mainly on legal obstacles to gender equality, second-wave feminism took on a much broader scope of the understanding of women in society. After having a taste of equality in the war years, women were reluctant to give it up and were inspired by writers like Simone de Beauvoir and Betty Friedan to fight for equal treatment in society.

Battles took place over the use of ‘the pill’, which became available in Australia in 1961 and gave women more autonomy over their sexuality and parental decisions, as well as miniskirts, and the right to go to the pub — which wasn’t fully legal in Australia until 1970.

In that same year, Australian feminist Germain Greer published her hugely influential The Female Eunuch which discussed the male domination of society and the resultant subjugation of women. With women gaining more financial power owing to widening employment opportunities, feminism continued to win legal and social rights, buoyed by huge Women’s Liberation protests.

A major win was the Conciliation and Abitration Commission’s ruling over equal pay for men and women in 1972. Following this legislation, women received, on average, a 30% pay rise. Changes in legislation came thick and fast in this era, including the pill being put on the PBS, benefits created for single mothers, and paid maternity leave for public servants. Women’s shelters were created in 1975 for those fleeing abuse, and the first Reclaim the Night marches were held in 1978 to protest violence against women.

In 1983, Australia signed up to the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Described as an “international bill of rights for women,” this key legislation had 30 articles intended to guide equal policymaking over political participation, health, education, employment, marriage, and family roles. Many worried it would signal the breakdown of society.

Third Wave Feminism

Emerging in the early 90s, third wave feminism was born out of an era in which feminist legal battles were largely considered to have been won. They critiqued the notion of who feminism was for — largely white, middle-class, wealthy women to exist in male-dominated institutions of power — and zeroed in on the individual rights of women to live as they chose to. Sexuality and sexual pleasure were key focuses of the movement.

During this period, marital rape was explicitly criminalised across all states and territories, starting again with South Australia in 1976 and ending with the Northern Territory in 1994. It was a long-fought shift that relied on the notion that women were essentially the property of men, having given themselves entirely to their husbands upon being married. These changes came at the same time as a host of other laws that expanded the definition of rape and sexual assault.

In 1990, Australia got its first female Premier Joan Kirner who led Victoria for two years. Sadly, she is still the state’s only female leader. In that same year, Lowitja O’Donoghue was elected as the first female leader of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission and in 1995 Jennie George became the first female President of the Australian Council of Trade Unions. Women’s History Month was launched in the year 2000.

The battle for abortion rights was a key one in the early 21st century as activists focused on state and territory laws. Prior to 2008, with the passage of the Victorian Abortion Law Reform Act, abortion could only be performed for medical or psychological reasons, although these legal requirements were increasingly loosely met up until this point. Abortion is still not uniformly allowed past certain points across the country and its access continues to be a source of concern.

Of course, you cant talk about feminism in Australia without talking about Julia Gillard. Australia’s first female PM became internationally famous for a speech she directed at then-opposition leader Tony Abbott after years of being attacked for her gender and the fact she was single and without children. Liberal MP Bill Heffernan claimed she was “unfit for leadership because she was deliberately barren.” It’s still a blistering run down and worth listening to in full.

Post-Feminism?

The 21st century also saw the supposed ‘end of feminism’, with some claiming we’re now in a ‘post-femnist’ era and that the movement is no longer necessary since women have achieved equality. Indeed, being a ‘feminist’ is still considered a dirty word in some circles, with the rise of ‘men’s rights’ whingers in response to aims at gender equality.

Conservative governments have responded in Australia by removing funding for organisations that support gender equality policies as well as crisis centres, women’s legal services, and domestic violence shelters. The belief behind these ideas is that the work is done.

This couldn’t be further from the truth, as a cursory glance at the gender disparity in economic power, sexual assault, and the appalling outcomes of sexual education in this country still indicate.

In recent years we’ve seen the rise of the #MeToo movement, with women coming forward to speak candidly about their experiences of harassment and attack, alongside a much greater understanding of the rights of trans women. None of this has come without the inevitable backlash, with the current ‘debate’ about drag queens in the US showing that gender and sexuality issues continue to be used as political weapons.

While an IWD cupcake is potentially the perfect symbol of this stagnation, women and their allies continue the legacy of fighting for equal treatment in society and under the eyes of the law.

Australia no longer has a Prime Minister whose own government oversaw the poor handling of an alleged rape case in Parliament and expected women to be grateful that they were not “met with bullets” when they marched. Progress has been slow and painful but it continues to move in the right direction, even if it doesn’t always feel like it at the time.

Related: The Gender Equality Issues We’re Still Fighting for in 2023

Related: It’s Not Just You, the UN Has Said 2023 Will Be a Tough One for Women

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.