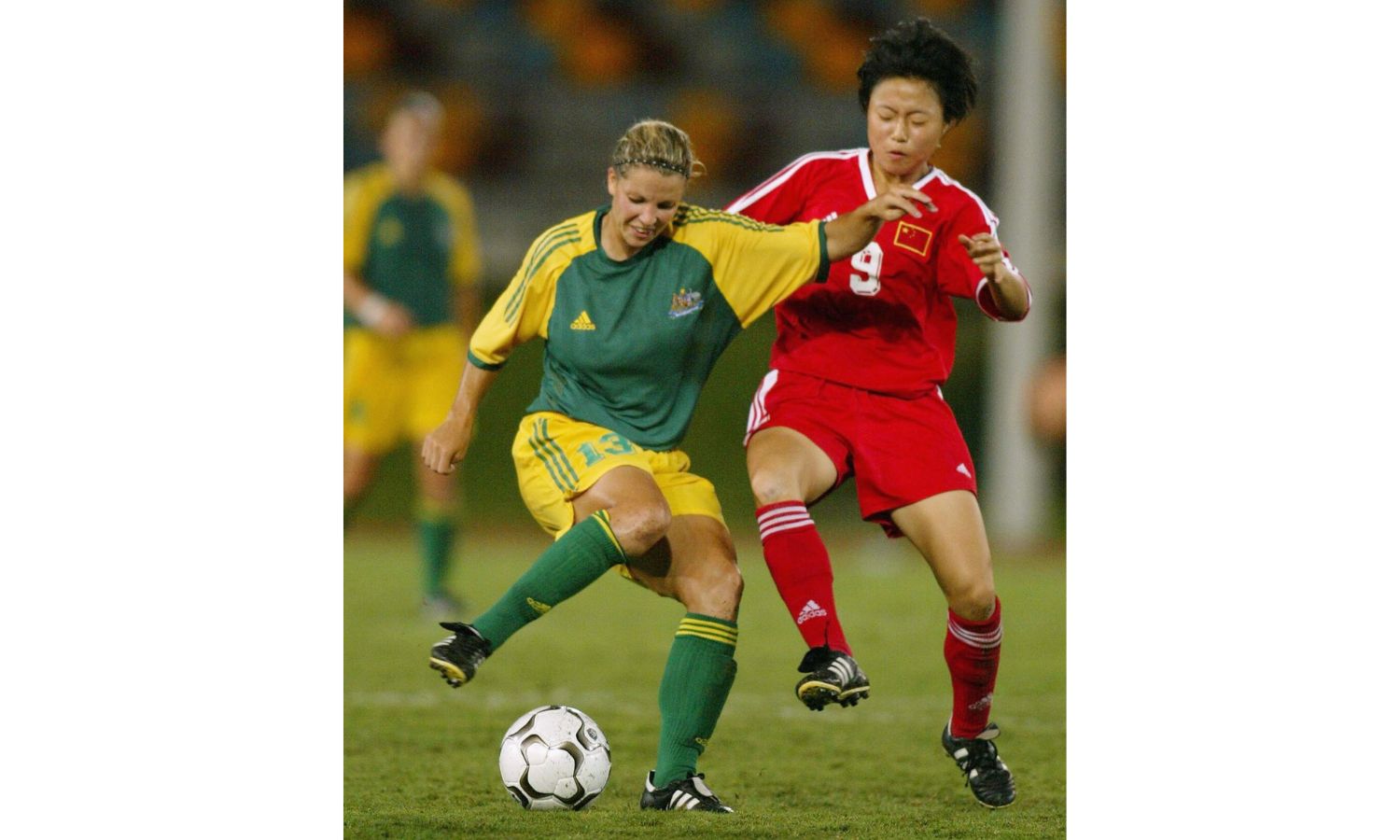

Australia is about to play host to a record-breaking sports event the likes of which the country hasn’t seen for a generation. But for a nation that prides itself on sporting achievement and fanaticism, our Matildas have faced an uphill battle for recognition.

“The first time I ever saw an actual Matildas team play, I was part of the squad,” former Matilda and Optus Sport commentator Amy Duggan told The Latch.

Growing up as a football fanatic, Duggan recounts a childhood full of fundraising, arguing her way into the boy’s team, and getting changed on the bus. Despite a bedroom covered in posters of professional players, it was only after winning a football covered in Matildas signatures at the age of 15 that she realised Australia even had a national women’s team.

“I was like, ‘Oh, you can do that?’ And they were like, ‘Yep’. That was the moment I made the decision that that’s what I wanted to do,” she said. Two years later, she debuted for Australia.

It’s not an unfamiliar story for female football players. While there is a belief that sport and politics should never mix, for women, football and fighting for equality have always been inherently entwined.

This reality is highlighted in a video released by the 2023 Matildas’ squad just days before the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup kicks off in Australia and New Zealand. In the clip, the current team champion the legacy of those who have come before them while pointing out the inequalities they still face.

“As Matildas… we stand on the shoulders of giants who have paved the way to afford the opportunities we have now, ” Forward Caitlin Foord said in a clip from the players’ union, Professional Footballers Australia (PFA).

With the @FIFAWWC kicking off this Thursday, our @TheMatildas have a message for those who paved the way. For those who broke down barriers and fought for progress. For the past. For the future.

For those within our football community, our fans, our sponsors, our politicians,… pic.twitter.com/gVImezbX30

— Professional Footballers Australia (@thepfa) July 16, 2023

All 23 players cite a catalogue of indignities that the women’s national football team have had to overcome throughout their history. These include playing tournament matches on artificial turf, having to do their own laundry, and receiving no prize money or even any pay at all.

For Matildas, as for so many female athletes, the battle on the pitch is only half of it. Heather Garriock, who played 130 matches for the women’s national team, spoke to The Latch about her up-and-coming struggle to even be taken seriously as a young girl wanting to play football.

“I think my fighting mentality and winning mentality came from those really formative years,” she said.

However, for both Duggan and Garriock, the battle is not an individual one. It’s about ‘leaving the jersey in a better place’ for future generations of women. Both will be cheering on the girls who play in their legacy as part of the Optus Sport coverage of the tournament, knowing exactly what it means to wear the green and gold — and the battles that have got the girls to where they are today.

Because the suppression of women’s football runs deeper than most imagine. Despite being the most popular sport in the world, there was a time when half the country was effectively banned from playing it.

Here’s how far the girls have come throughout the history of the game and exactly what the tournament, kicking off on Thursday, will mean.

The History of Women’s Football

Women have likely played football for as long as the game has been around. The sport, comprised of a ball and a flat playing ground, is recorded throughout history across the world, possibly as far back as 7000 years ago.

Football was codified in its modern form in the mid to late 19th century in England — and women were there from the start. The first international women’s match was played between England and Scotland in 1881 and there are reports of “ladies” teams being formed right after Australia was federated in New South Wales in 1903.

During the First World War era, Women’s football took off. Men had gone off to fight in Europe, and women went into the factories making weapons to support them. As a social hobby, they formed football teams, which became the only morale-boosting game in town.

In 1921, North Brisbane beat South Brisbane 2-0 at The Gabba in front of 10,000 people — marking the first women’s public football association match in Australia. In the UK, the year before, 53,000 people came to watch Dick, Kerr Ladies play St Helens at Goodison Park in Liverpool. 14,000 fans couldn’t even get into the stands. It was a record attendance for the sport that was unbroken for nearly a century.

The crackdown

But the popularity of the games quickly drew the attention and jealousy of the authorities. The amateur girls’ teams often played charity matches for organisations tied to the suffragette movement and working-class causes. It couldn’t be allowed.

In 1921, the Football Association in England banned women from playing football in their facilities — effectively ending female participation in the sport. The FA’s Consultative Committee stated that:

“Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, Council felt impelled to express the strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and should not be encouraged.

“The Council requests the Clubs belonging to the Association refuse the use of their grounds for such matches.”

A similar sentiment was adopted in Australia. A football committee in 1922 found that football was medically inappropriate for girls to play — it may have too much impact on their all-too-important ability to give birth. Women would be better off sticking to swimming, rowing, cycling, and horseriding, the report concluded.

It was against this backdrop that women’s football began to fall out of favour. The Queensland Football Association stopped playing women’s games after 1922, and the NSW Football Association cut back their support on women’s games through the 1930s.

The Rise of the Matildas

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the sport started to reemerge after decades of bans and setbacks. Trailblazing women like Elaine Watson have been credited for resurrecting the game. Over three decades, Watson played, coached, and managed the women’s game at every level, eventually leading the development of the 1988 FIFA Invitational in China, a precursor to the creation of the Women’s World Cup in 1991. Today she is known as the matriarch of women’s football in Australia.

In 1995, the Australian Women’s National Football team qualified for their first-ever FIFA Women’s World Cup. Identity and distinction however was a issue, with the team being referred to as ‘the Female Socceroos’ in the press. SBS and the Australian Women’s Soccer Association (AWSA) ran a competition to find a better nickname, and ‘the Matildas’ was settled on after the Banjo Patterson song.

Despite the uplift in national and international recognition, Duggan said the contrast between the treatment of the Australian team and other national teams at the time was eye-opening.

“I was meeting players that were full-time athletes and players that had sponsorships, you know. They were living the dream,” Duggan said of her first US tour.

“We got police escorts and proper clothing and full kits and our boots supplied. The trip was obviously paid for as well. These were things that we would not necessarily have been used to. It was mind-blowing.

“At the time, I just couldn’t fathom why it wasn’t like that in Australia. Ever since then, I’ve known it was a possibility. We’ve just taken 20 years to catch up”.

When Sydney was selected as the host city for the 2000 Olympics, and women’s football would be included in the games, Australia did not even have a national female tournament. $1 million in annual funding was quickly organised and used to create the Women’s National Soccer League (WNSL).

By 2000, the Matildas made their Olympic debut. However, the opening game against Germany wasn’t even covered on national television at the time. Australia did badly, losing all three games, and the WNSL folded in 2004 alongside the men’s NSL. It didn’t restart until the W League was founded in 2008, now the A-League Women, three years after the men’s A-League was created.

The battles off the pitch

The national team kept going, despite the chaos and confusion. Garriock cites the influence of manager Tom Sermanni and the fact that few players played in international clubs as building the culture of the team today.

“We were a family. We operated like a family, spent a lot of time together, and, you know, I felt a belonging within the national team,” she said.

Under Sermanni’s second term as manager from 2005 to 2012, the Matildas rose from 15th in the world to 9th. And yet, Garriock notes she and fellow teammates were still having to fight for the basics.

She didn’t have the support she needed when returning to the team during the time after her first daughter and ended up taking Football Federation Australia to court over childcare coverage during the 2013 national tour. The regulations at the time were described by the PFA as forcing women to choose between their family and their career — something not asked of the men.

“[That] was actually not for me; it was for a change of policy and the way in which the Federation looks at women and professional sports people,” Garriock said.

It’s just one example of the off-the-pitch battle that Garriock and her teammates were fighting while representing the country. Together with the PFA, she and her colleagues were able to negotiate better standards of play contracts for female footballers with the Football Federation, even at the risk of being considered troublemakers.

“We deserved better. We deserved minimum pay; we deserved standard play contracts, we deserved our washing being done on tour, we deserved internet. But this could have come at a cost, and that’s the selection cost,” Garriock said.

“I think moral courage is really important in the world today because it’s important that we are not just people and players that are here to do what we’re told”.

As a current board director of Football Federation Australia, Garriock said the organisation is now one she’s extremely proud to represent. Indeed, these were not battles fought in isolation. System change within women’s football has been a long-standing need.

A year after Garriock’s case was settled, the game’s all-time top goalscorer, Ada Hegerberg of Norway, was beginning a campaign of protest against inequality in the sport. Upset over the lack of respect shown to female players by the Norwegian Football Federation, the first-ever Ballon d’Or Feminin winner ended up boycotting the 2019 Women’s World Cup. 2023 will be her first time playing for the national team in six years.

The 2023 FIFA World Cup

The 9th FIFA Women’s World Cup will be where we see the scales of equality really begin to tip back into balance.

This will be the first in which 32 teams compete — the same number as the men’s. The games have already had to shift stadiums due to overwhelming ticking demand and, unlike the 2000 Olympics, all 64 games will be live streamed on Optus Sport.

The team will have their laundry done, they’ll be playing on grass, and they’ll be paid. These might sound like basics, but for the girls growing up to play in the early years of the Women’s World Cup, the spectacle is almost unrecognisable.

“I think the biggest crowd I played in front of in Australia was about 10,000 people at Marconi [Stadium, Sydney] against Italy, and I’m pretty sure most of them were going for Italy,” Duggan quipped.

“How wonderful it is that our sport has progressed to the stage where you can be a full-time professional footballer.

“Because for so many people growing up, I think that’s all we ever dreamed of. And it was an option for men, but it was never an option for women.”

Pay Still an Issue

Still, she acknowledges that there is still work to be done. At present, Australia has the most respected team of national women’s footballers we’ve ever had, in both the social and sporting realms. And yet, they’re still having to fight.

Despite over a million tickets already sold, making this the largest women’s sporting event ever, prize money for the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup is $483 million less than that of the men’s.

“FIFA will still only offer women one-quarter as much prize money as men for the same achievement,” Matildas midfielder Tameka Yallop said in the above video.

Pay is a consistent theme, as Duggan notes above. In the W League, it’s expected that players will have to have a part-time job in order to fund their athletic ambitions.

“A lot of players are still, you know, part-time professionals. Training like full-time professionals, being paid like part-time professionals,” Duggan said.

That said, salaries this year are three times higher than they were at the 2019 Cup, and FIFA are eyeing gender parity for prize money in 2027. The $45,000 that each player will receive, outside of prizes, for playing in the 2023 World Cup is already more than double the average women’s club salary — a bittersweet statistic.

A Celebration of Progress

Despite these continued difficulties, this is ultimately a time to celebrate the progress made. Our national team have players renowned the world over as best-in-class, and we have a genuine opportunity to win our first-ever football world cup — on home soil, to boot.

“I grew up looking up to Mia Hamm, who was the best in the world, from the USA,” Garriock said.

“And now, the Mia Hamm of the 2020s is Sam Kerr, and she’s an Aussie. We’ve got 25-odd million people in our country, and she’s the greatest footballer on Earth. That’s just so unbelievable, and I think it just shows how globally Australian football is respected”.

There is a real sense of culmination about these games. As Matildas’ defender Alanna Kennedy says in the above video, “For us, this World Cup is a celebration of that progress that we’ve had to earn every step of the way.”

What comes next is all down to the players on the field — and the 1.5 million ticket holders and their multiple millions of counterparts watching through a screen. It’s certain to be a monumental occasion. The country won’t know what hit it.

“I don’t think Australia knows and understands what it’s about to see and embark on. It is the greatest game in the world. And it’s a global game,” Garriock said.

“Soccer has never been the number one sport in Australia, but I think non-football Australians are going to see what global football is all about”.

Related: Albo Suggests Australia Could Score a Public Holiday If the Matildas Win the World Cup

Related: Australia and New Zealand Are Limbering Up for the FIFA Women’s World Cup

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.