This week marked 30 years since the publication of the four-year Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. The investigation found Indigenous people were “grossly over-represented in custody” and made a total of 339 recommendations to correct the myriad of issues uncovered.

The report looked at the period from 1980 to 1989 to investigate the 99 deaths of Indigenous people in the custody of police, prisons, or juvenile detention facilities. It concluded that the causes of death were “extremely varied” and that there was no “common thread of abuse, neglect, or racism” between the deaths. However, the report stated that the social conditions in which Indigenous people were living contributed to their deaths by nature of being in a disadvantaged position.

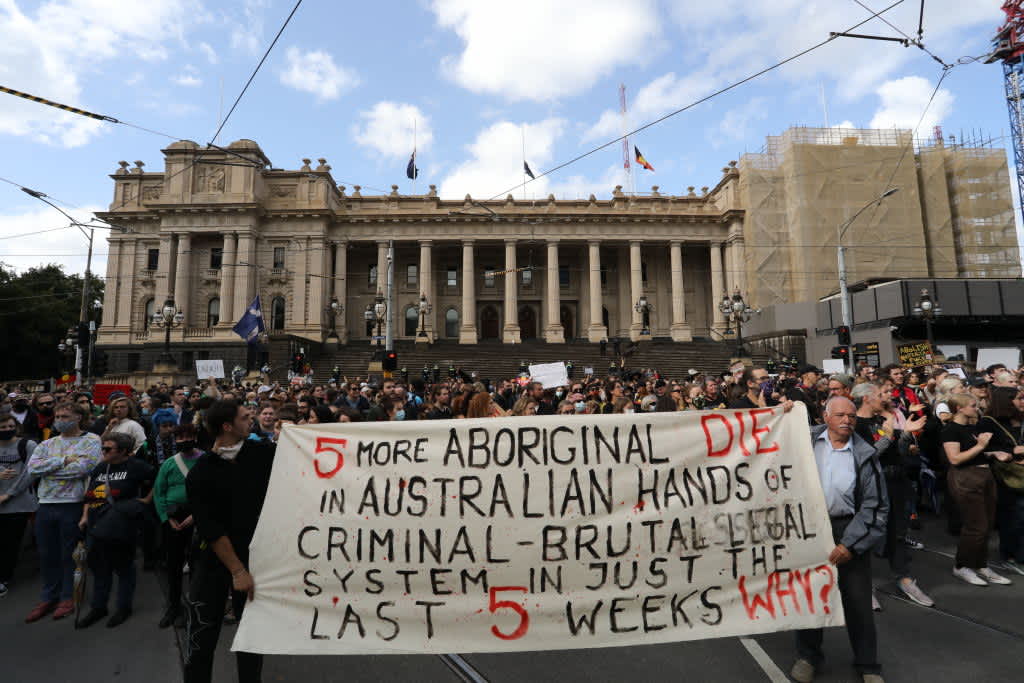

Since the damning report was published, an additional 474 Indigenous people have died in custody, with five people having died in a little more than the past month alone.

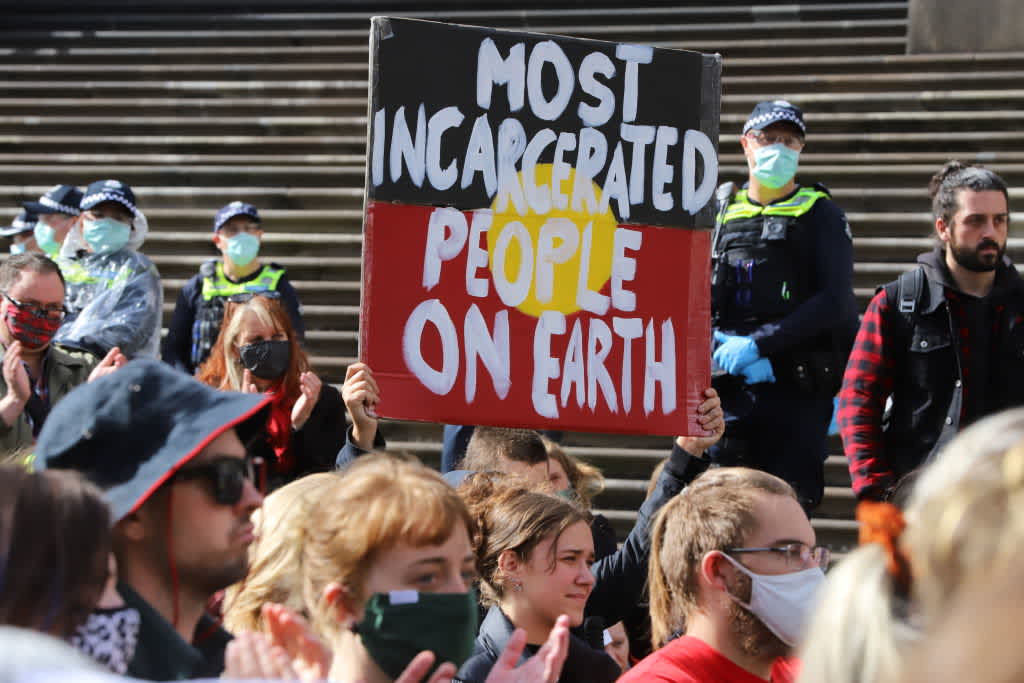

Last year, the Black Lives Matter movement took on a new dimension in Australia as thousands of people marched across the county to protest Indigenous deaths in custody and police treatment of the Indigenous population. While the culture is shifting, this is still clearly a necessary conversation that we need to continue having.

So, in the three decades since the report was published, exactly what has changed for the Indigenous population, our society, and the systems of criminal justice that are supposed to protect us?

What Were the Recommendations?

The Royal Commission was established in 1987 in response to public outcry over the cases of 88 men and 11 women who had died in custody over the previous decade. The youngest of these was aged just 14.

The Commission found that Indigenous people died in custody at the same rate as non-Indigenous prisoners, but that they were far more likely to be in prison. It also identified the removal of children from families – a policy pursued in some states until 1969, though still happens in “alarming numbers” today – as a significant precursor to high rates of imprisonment.

It made 339 recommendations to correct the issues contributing to Indigenous deaths in custody. These included strategies for directly preventing deaths in custody – by removing “hanging points” in cells, for example – to structural improvements in health, education, economic opportunities, housing, land rights, and reconciliation.

Some of the recommendations included:

- Abolishing the offence of public drunkenness – used to charge Indigenous people in higher proportion than non-Indigenous

- Ensuring the principle of self-determination is applied in any policy or program which will particularly affect Indigenous people

- Giving Indigenous media organisations “adequate” funding

- Encouraging police to caution young people, rather than arrest them

- Police to take “all possible steps to eliminate violent or rough treatment or verbal abuse of Aboriginal persons”

- That police take steps to “eliminate the use of racist or offensive language, or the use of racist or derogatory comments in log books and other documents”

- Governments and other organisationa discuss strategies to reduce the rate at which Indigenous youths are involved in the criminal justice system

The final recommendation was for political leaders to recognise that “reconciliation between the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities in Australia must be achieved if community division, discord and injustice to Aboriginal people are to be avoided”.

What Has Changed?

A 2018 Deloitte review of the report looked into how the Royal Commission’s recommendations have been implemented. It found that of the 339 recommendations made, only two-thirds of these have been adopted. While the rates at which Indigenous people died in custody had halved, the rates of Indigenous incarceration had doubled.

The overarching theme of the Commission’s recommendations is the need to reduce the number of Indigenous people in custody, something that has clearly not happened.

Deloitte’s report found recommendations aimed at breaking the cycle of imprisonment and diverting people away from prison had the lowest rates of implementation nationally.

64% of the recommendations had been fully implemented, 14% were mostly implemented, 16% were partly implemented, and 6% were not implemented at all. Tasmania had the lowest rates of implementation.

The report found that monitoring deaths in custody has “reduced over time” across all jurisdictions, and reporting of data about police custody was “an ongoing issue”. Some jurisdictions still failed to perform regular in-person cell checks of people in custody, particularly at police watch houses.

It also found that prison safety had improved significantly but Aboriginal mental health workers ought to be used more prevalently in jails.

“While there have been positive steps, it is clear that further work is still required to address the disproportionately high and growing rates of incarceration among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people,” the report said.

What Happens Now?

With continued focus and attention turning to the dismal failings of the state to keep Indigenous people out of the criminal justice system, pressure is continuing to mount on governments at the state and federal level to enact effective change.

The Guardian puts the figure of Indigenous people who have died in custody at 474, though the difficulty in getting clear information makes it hard to be accurate about this.

High-profile deaths since the 1991 Commission include David Dungay Jr, a 26-year-old who was held down by police while saying “I can’t breathe,” Ms Dhu, a 22-year-old who died in a police cell after she did not pay parking fines, and Nathan Reynolds, a 36-year-old who died from an asthma attack in prison after an “inadequate” emergency response.

Five more Indigenous people have died in custody over the past few weeks, re-igniting the debate and increasing calls for state action.

The families of 15 people who have died in custody spoke at a rally in Sydney last weekend, demanding action from politicians. They called for the full implementation of the Royal Commission’s recommendations and the raising of the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14.

“The spiritual and emotional unrest of knowing that our loved ones won’t be coming home is immeasurable. We live with this ongoing trauma day to day,” the families said in a joint statement.

“Our communities have had the solutions to end this injustice for 30 years but Governments have chosen not to prioritise saving Black lives. Enough is enough.”

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.