Welcome to The Great De-Vape, a three part series from The Latch‘s News and Culture Editor Jack Revell, drug policy nerd and author of the Drugs Wrap newsletter.

In part one, we looked at the changes to vaping laws that are coming this Friday, 1 October and why they are being made.

In part two, we examined the health impacts of vaping.

In this third and final part, we look at the impact that the new policy will have on smokers, vapers, and society at large.

From tomorrow, Friday, 1 October, vapes will now be harder to access than cigarettes. While the Therapeutic Goods Administration — Australia’s medicine’s regulatory body — has said that this will prevent young people from accessing nicotine, it’s hard to square with the fact that tobacco remains a consumer product, available at over 20,000 outlets across Australia.

Experts have warned that this change will push those using the devices back to tobacco if access is made more difficult for vaping products than the alternative and that Australia will have missed a monumental opportunity to prevent some of the 24,000 deaths caused by smoking in this country each year.

As places like the UK and the US embrace vaping as a positive shift in being a less harmful way to consume nicotine, Australia has become the most restrictive nation in the West.

What happens now will put this policy change to the test. If reducing the harms caused by nicotine was the aim, it seems unlikely that this measure will achieve those outcomes.

A Prescription for Harm Reduction

One of the strangest aspects of this whole situation is the fact that nicotine has never been allowed to be sold in corner shops or online to anyone under the age of 18. If the target of these new changes was to curb an increase in young people vaping — something there is little evidence for — then regulation of these outlets might have dealt with that issue in a more nuanced fashion that didn’t impede the rights or health of adults.

I put the question to NSW Police, who informed me that “NSW Police do not police the use, sale or carrying of e-cigarettes,” directing me instead to Liquor and Gaming. This is an interesting response as it suggests that those who vape in public are unlikely to attract the attention of police post-ban and likely won’t be asked to produce a prescription for their device. Of course, as policing irregularities seen during lockdown in Sydney have shown, officers may not always understand or stay with their remit.

Liquor and Gaming informed me that this area would be the responsibility of NSW Health who issued the following to The Latch:

“NSW Health has a strong e-cigarette compliance and enforcement program targeting retail stores.

“From 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021, NSW Health seized over 80,000 e-cigarettes and e-liquids containing nicotine or labelled as containing nicotine. NSW Health has successfully prosecuted 22 retailers since 2015 for selling e-cigarettes or e-liquids containing nicotine.

“It will remain illegal for all retailers, such as tobacconists, convenience stores and service stations, to sell e-cigarettes and e-liquids that contain nicotine.

“Under the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1966 illegal supply of a prescription medicine carries a maximum penalty of $1,650 or 6 months imprisonment, or both.

“NSW Health continues to work with a range of stakeholders, including NSW Police, the NSW Department of Education, schools, and non-government organisations on the issue of e-cigarette use amongst young people.

“This includes public awareness and education campaigns, quit smoking support, compliance and enforcement of strong smoke-free and retailing laws, and targeted programs for vulnerable groups with high smoking rates.

“NSW Health has increased the number of inspectors with powers to seize e-cigarettes.

“NSW Health regularly communicates with retailers in NSW to remind them of their obligations under the law”.

Anyone who wishes to continue vaping after tomorrow will need to obtain a prescription to either import nicotine or purchase a vaping device from a pharmacy.

There are a few issues here. First of all, getting hold of a prescription is going to be difficult.

Dr Alex Wodak, board member of the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, says that, at the moment, just 71 GPs of the 110,000 in Australia have stated that they’re prepared to prescribe nicotine.

“Of those 71, only 14 have allowed their names and contact details to be publicised while we’ve got at least 520,000 vapers who will need a prescription for vaping nicotine and some of the two and a half million smokers that want to switch to vaping will also need a prescription. They’re meant to get that from 71 doctors, only 14 who have gone public? It’s nonsense.”

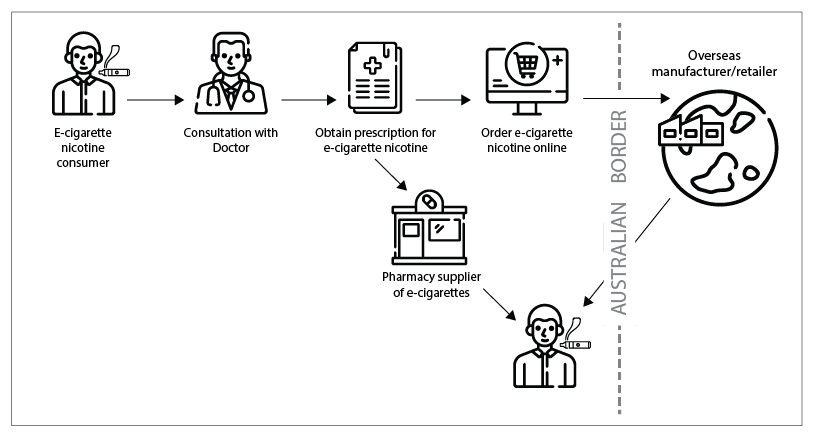

GPs will only be able to prescribe nicotine if an individual can show that they have tried multiple alternative smoking cessation treatments without success. If they can, the GP will need to assess the individual’s nicotine consumption and provide a three-month script to allow them to import nicotine from overseas in a quantity consistent with their three-month usage needs.

In a statement to The Latch, the TGA have said that they will work closely with the Australian Border Force to detect and assess importations of nicotine, requiring those ordering the products to produce their prescription. If the individual is unable to, they may be liable to pay penalties of up to $220,000.

Those supplying nicotine-containing vaping devices to an individual without a prescription can face fines of up to $1,110,000 for individuals and $11,100,000 for corporations.

The procedure will work something like this:

Devices sold in pharmacies are not regulated by the TGA, like most pharmaceutical products, but instead, fall under a new category created by the body that sets minimum safety and quality requirements nicotine vaping products.

This will ensure that products don’t contain unnecessary toxins and hold proper labelling, but Dr Colin Mendelson, co-founder of the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, told The Latch that this will also result in a more limited range of products being available at a higher cost to the consumer.

“It really limits people’s choices and the thing about vaping is that there is something for everyone but you’ve got to find it. Vapers have to find the right device, the right flavor, and the strength that works for them and this new system isn’t something that’s going to work for a lot of people”.

“In every other western country, it’s not a medicine, so the TGA shouldn’t be managing it, the ACCC should be. This is a consumer product, replacing an existing consumer product.”

Drug policy has a long and sorry history of unintended consequences arising from the actions of blanket prohibitions and tough penalties imposed often in response to moral panics.

One of the unintended consequences of these changes will likely be an expansion of the nicotine black market, already active on social media like TikTok, and the stockpiling of nicotine by vapers preparing to wait out the new changes.

“That’s not a good thing either,” Mendelsohn said, “That creates large volumes of high concentration nicotine lying around in liquid form.”

Vapers who are clued up on the changes have had months to prepare and many on social media note having stocked up enough liquid nicotine to last them for years.

VapourEyes, a New Zealand company and one of the leading distributors of online nicotine to Australia, has filled 20,000 orders for nicotine in the past few weeks, with only 50 prescriptions for the chemical provided to the site.

The most serious unintended consequences of the new changes of course will be people who use vapes going back to smoking because they simply find the new policies too difficult and too confusing.

“It’s so hard to find accurate information about vaping in Australia. For smokers who want to make the switch, it’s very hard for them to get information and to access these products from scratch,” Medelsohn says.

“If you’re already a vaper, you kind of know what’s going on and maybe you’ll be willing to jump through the hoops, but starting from scratch, it just seems too overwhelming.

“You can’t just walk into a vape shop and buy a product. We’ve got 3 million smokers for whom it’s not accessible”.

While vape shops, the kind with the rows and rows of intimidating bottles and shiny mechanical devices often run by large men with stretched out ear-lobes, won’t be going anywhere, it’s going to become a lot more difficult for them to explain to a person looking to try vaping and come off cigarettes exactly what they need to do and how to do it.

“I’ve talked to a lot of vapers, and some people have said to me; ‘If I can’t get my nicotine liquid, I’m not gonna go to the doctor. I’m not sick, I’m just gonna go back to smoking’,” Mendelsohn said.

What Happens Now

The outcome of the new rules will make what is essentially a harm reduction tool harder to access than the poison available in most supermarkets.

What happens next is anybody’s guess, but the signs do not point to a positive health outcome for Australians.

For Dr Wodak, the fight is not yet over and he believes those in government who have facilitated these changes will pay the price at the next general election.

“There are three and a half thousand vapers per electorate, roughly speaking, and their families, and for them, it’s a huge issue,” Wodak said.

“When people have been chain smokers who have been trying for decades to quit, and have been unable to do so, along comes vaping and they quit within days. And then somebody takes vaping away.

“For them, it’s going to be the single biggest issue that will decide their vote, and in some electorates, it could even decide who wins that seat. I think that’s where we’re gonna see a lot of action”.

For Wodak personally, as a leading harm reduction advocate with a keen focus on tobacco; “there’s not much we can do but watch the slow-motion train crash”.

Australia, as a society, has once again demonstrated that it just isn’t ready to have a mature discussion around the pleasures that people get from drug use. If drugs weren’t pleasurable, people wouldn’t do them.

While most Australians will agree with that argument if you’re talking about alcohol, anything considered a “drug” is branded as immoral and the habit of social degenerates.

Vaping, unfortunately, has fallen afoul of a century of stigma and religious moralising that continues to sideline and denigrate people from all strata of society, particularly the most vulnerable.

If the new laws prevent young people — already the most likely to be experimenting with drugs, including tobacco — from picking up a vape and becoming hooked on nicotine, that will be a good thing.

But to come at the cost of declining smoking rates and the easy substitution for Australia’s nearly 3 million smokers to a means of enjoying nicotine in a far less harmful fashion is an appalling trade-off.

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.