Welcome to Dig Deeper, a content series allowing you to dive as deep as you like into topics that are underserved in the current media landscape but need and deserve more coverage and attention.

Its purpose is to shed light on important community-based issues facing minority groups. To start with, we’re having honest and open conversations around January 26, the national mood and changing the date.

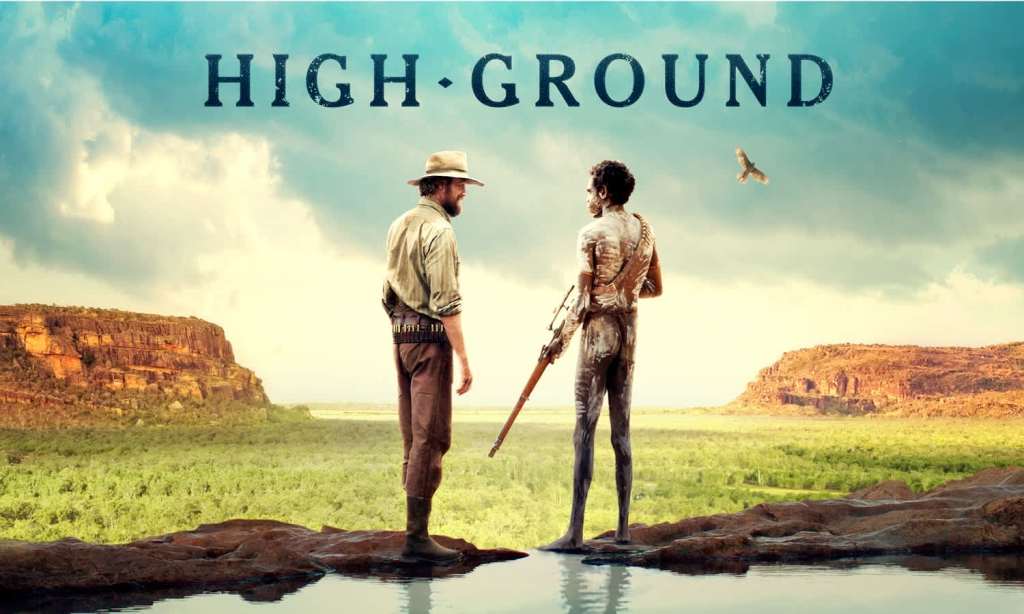

A “Northern” is how director Stephen Maxwell Johnson describes his new film, High Ground, playing on the great American tradition of shoot-em-up cowboy movies we’ve come to know and love from Hollywood.

As COVID caused a mass exodus of the great and good from Tinseltown to the sandy shores of Australia, it’s not hard to imagine that the great Aussie Northern could become a genre unto its own – particularly when the films are of this high calibre.

High Ground sees Simon Baker (The Mentalist) as a disillusioned officer in 1920s Arnhem Land trying to balance duty and justice on the bloody frontier of colonial expansion.

Indigenous elder Witiyana Marika, of Yothu Yindi fame, tries to steady the ship as worlds collide and violence and oppression are wrought upon the land.

It’s a gripping man-hunt story tracked through the awe-inspiring Northern Territory, with Aussie screen legend Jack Thompson, Underbelly star Callan Mulvey, and newcomer Jacob Junior Nayinggul.

The film pulls no punches in its raw depiction of life during settlement and grapples with piercingly relevant themes of ownership, cooperation, and the soul of the nation and its connection to the land it comprises.

Beautifully shot, it watches almost like a tourism piece for the Northern Territory. The stunning scenery is however contrasted with incredible violence and brutality.

“I wanted it to be visceral”, Johnson told The Latch. “I wanted it to be immersive. I wanted the landscape and the country to be very much a character in the film that’s representative of peace, a disturbing peace”.

“Essentially, it’s representative of the oldest living culture and human connection to the land on Earth. I’ve always wanted land to have a very, very strong presence and connection to the storytelling.

“When you see the film in a cinema, you become aware of all of the sounds of the wind and the land and the creatures and the birds and life itself in that way, because it’s all connected”.

The movie opens and closes on a towering rock structure standing high across the desert which acts as both the physical and metaphorical high ground.

“That rock is in fact one of the most sacred sites in Western Arnhem Land because it’s where the Djanggawul sisters came to rest. One looks east and one looks west and if you look carefully on that first rotation at the beginning of the film, you can actually see two faces very clearly in the top of the rock.”

“That’s what’s being sung about at the start which sets up this whole idea of creation and the East and the West and ancestral beings moving across the country at the beginning of time”.

Although there is some Indigenous music in the film, generally it’s a very quiet affair, reflecting the stillness and the wildlife of the bush.

“It really is just about trying to put the audience in place, on Country, and in the story itself. It’s about needing to listen, needing to think here and be affected by all that is going on; human, land, animal. I’m just hoping that the film offers a new perspective, a new way of thinking about things”.

The film’s narrative is led by Gutjuk, a young Aboriginal man torn between worlds.

“It’s trying to explore and grapple with our history which is very difficult, misunderstood, misrepresented, and obviously is one of the greatest missed opportunities. And me as a filmmaker, we as a team, collaborated with the Elders right across Arnhem Land and have come together to create this story and put it out there for people to consider”.

The story itself, though fictional, is a composite of the endless historical events ending in bloodshed and massacre – including some that happened to Witiyana’s own family.

“It is a fiction, but it’s a fiction to tell a deeper and a much more powerful truth about what happened”, Johnson explains.

“There are some very, very immediate incidents in Arnhem Land that are very closely connected to Witiyana and a lot of other people who were involved in the making of the film that was also inspiring to the story.

“It’s right to say it’s been inspired by true events and characters in our history. We’ve put out what we believe is a very true and honest take on circumstances that were taking place back then.”

Misunderstanding and missed opportunity is a recurring theme throughout both the film and, as Johnson notes, our own history too.

“We’re trying to make it accessible for people. We’ve got to stop being apologetic all the time or else we’ll never reconcile in this country.

“We’re trying to get into the nitty-gritty in a way that’s confronting but it doesn’t push you away. It draws you in, and it lets you want to understand and feel the story and feel our history in a different way,” he says.

“Hopefully it will lead to a much more robust and honest and open and effective discussion about how we can move forward in this country together. It’s a very precious and special thing that we have, the language, the dance, the yarns, the ceremonies. They are still alive but they’re rapidly disappearing. Genocide is still taking place in this country and it is a shame. It is a shame upon this nation that that is continuing to happen. And we have got to stop blaming and we’ve just got to all start taking responsibility for this very special thing that we all ultimately are a part of and can learn from”.

While the film deals with anger, resentment, and retribution, at its core it has a message of peace and forgiveness. While Johnson says he doesn’t want his film to be a polemic, dealing with issues like these and choosing to release the film just days after the annual Australia Day/Invasion Day debate has come to a head is inherently going to draw questions of politics.

“Until that is truly recognised and truly accepted and honored, I don’t think we can move forward”

“I think there is such ignorance and such blocking and not wanting to own and really understand our history. And I just hope this can just open up that conversation again, and we can all start thinking about it in different ways and just opening our hearts more”.

“I think until we just get the roots of the matter right – that this was a land occupied by Aboriginal people for a very, very, very long time, as long as time can remember. Until that is truly recognized and truly accepted and honoured, I don’t think we can move forward”.

“The very least we can do is enshrine that voice for all of our states and our Constitution. We need to start getting really honest and truthful and robust about what we do and how we respond to that. It’s not going to go away. It’s there because it’s absolutely an inherent part of who we all are.”

With the call Black Lives Matter debate continuing to reverberate around our social media feeds, it seems like Johnson and his team have lucked-out in their timing.

“I think it’s been an unprecedented time on this planet for every single living human being to understand our vulnerability and the fact that we were exposed, we’re very exposed.

“I just hope that this film can just be a part of whatever energy force is around and acting and being considered by people at the moment and it will be accepted and reflected upon in positive ways.”

While the film depicts a lot of the violence and anger that colours our history, it also offers a path forward.

“I don’t have the answer”, Johnson says, “but I do feel strongly. We do not need to fear this whole thing. We need to stand strong, listen, learn, share, care and really understand things in a different way.”

“No one’s going to lose anything, but we’re all just going to gain actually. And we need to start having serious conversations and stop blocking that process.

“There’s all this beautiful language, all these beautiful stories, all these incredible deep connections to country and the earth that are just out there, alive and well, and rich and beautiful.

“Let’s not let anger get in the way of listening. Let’s just allow ourselves to be calm and vulnerable and just let this all in now and know that we’ll be good. We’ll be better for it. We’ll all be better for it.”

High Ground is now available to stream on Stan.

Related: How to Know What Indigenous Land You’re On

Related: Know Better, Do Better: The Best Aussie Podcasts to Educate Yourself on Indigenous History

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.