The term ‘elevated horror’ has become a permanent fixture in film critic circles over the past several years and was first used after the release of A24 produced films The Witch and Hereditary, and the Blumhouse-produced Get Out, which resulted in a new era of horror filmmaking.

As to who coined the term “elevated horror” is unknown, yet what is certain is that this eye-rolling rebrand of the horror genre is snobbish at best and condescending at worse.

Perhaps more maddening is that critics and audiences who have embraced the “elevated horror” tag seem to be suffering from a case of selected amnesia when it comes to the macabre majesty that is horror cinema. From F.W. Murnau’s 1922 horror classic Nosferatu to the recently released Osgood Perkins directed Longlegs, horror cinema has proven to be a diverse and ever-evolving genre of film where scuzzy grindhouse fare (Maniac, Last House on the Left) rubs shoulders with high concept chillers (The Exorcist, Hellraiser.)

Take the filmography of master horror filmmaker John Carpenter. After establishing the groundwork for the slasher movie with 1978’s Halloween, Carpenter would go on to deliver perhaps the best example of sci-fi horror in 1982’s The Thing, and then delve into religious horror with 1987’s Prince of Darkness. Neither film was more “elevated” than the other. They are just, well, great horror movies.

When Carpenter was asked about the term “elevated horror” during an interview with The AV Club, the notoriously plain-speaking director responded: “I don’t know what that means. I can guess what it means, but I don’t really know…There’s metaphorical horror. But all movies have … they don’t have messages. They have themes. Thematic material, and some horror films have thematic material. The good ones do.”

Perhaps Carpenter tapped into the root of this whole “elevated” madness: the annoying tactic of critics, studios, and filmmakers to pretentiously declare that their horror movie is above the genre because it addresses social and political themes. Again, many forget that horror has long been a genre that has addressed all matter of social and political topic be it populist or taboo.

Take Get Out as an example. The directorial debut of filmmaker and comedian Jordan Peele, Get Out not only became a box-office success and critical darling, but also that rare horror movie that snagged Oscar gold, no doubt for its “brave and bold” commentary on race relations in the US.

True to the pretentiousness of some film critics, Get Out was lauded for its social-justice commentary, thus making it ‘elevated’… yet hardly original, with the topic of race a staple in horror for quite some time, as exemplified in George A. Romero’s groundbreaking Night of the Living Dead, Bernard Rose’s Candyman, and Jonathan Demme’s Beloved (among many others.)

Filmmakers, of course, have no qualm in selling their film as more than just another horror movie. Ari Aster, the director of Hereditary and Midsommer (films that owed much to The Exorcist and The Wicker Man, respectively), admitted as much during an interview with Cult MTL when asked about the elevated horror movement.

“A lot of horror films are very cynically produced, and I don’t go to see every horror movie because it’s a crapshoot. A lot of these films are being made in order to make a quick buck; they’re being made cheaply, but they’re also made without seriousness of purpose,” said Aster. “But that’s nothing new; we had B-movies in the 1950s… It’s a difficult question in some ways, because I guess if I’m going to make a horror film, I want it to fall in that weird subgenre of ‘elevated horror’. And for that reason, when I was pitching the movie around, I was describing it as a family tragedy that warps into a nightmare.”

In the end it is the pitch, the marketing, the sell, where you will truly find the ‘elevated’ in the horror. A24 has cornered the market in making their horror releases appeal to both mainstream and art-house cinema fans. A24 movie trailers are especially strong in teasing the moody and macabre nature of their horror film slate and are almost worth the price of admission alone.

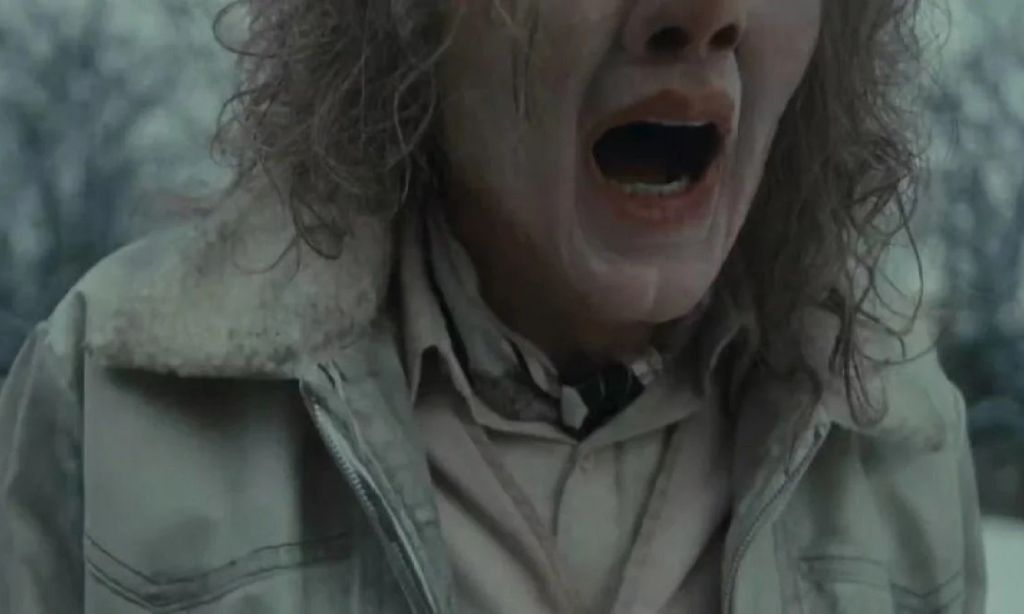

Taking things further is another boutique film studio, Neon, which released the horror box-office surprise Longlegs in July. Vital to the success of Longlegs was the long-game approach of the marketing by Neon, with a string of teaser trailers that prioritized mood and intrigue and – above all – mystery sending horror fans’ hearts-a-flutter. Combined with several critics labelling Longlegs as “the scariest movie of the year” (an often-used phrase) and Longlegs became one of the most anticipated films of the year….and one of the most overhyped, with the Osgood Perkins directed film retreading steps previously laid by superior detective horror movies – The Silence of the Lambs, The Exorcist III – that came before it.

The horror film genre features some of the greatest movies of all time: The Exorcist, The Shining, Nosferatu, Jaws, Frankenstein, and so many more. It is a genre of film that boasts filmmaking creativity and ingenuity, and a daring to delve into thematic territory that filmmakers of other genres would not dare to tread. In many ways horror is cinema personified. In no way does it need “elevating”. What does, however, is the film education of critics who should know better.

Related: Dancing for the Devil and More Must-See Netflix Documentaries

Related: The Latch Selections: The Best and Most Anticipated Movies of 2024

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.