It’s a summer night in New York, 1973. August 11th to be specific. At 1520 Sedgwick Ave in The Bronx, a crowd of neighbourhood pals have gathered for a birthday party in the building’s rec room.

Playing music is a chap named DJ Kool Herc who spins records on not one, but two turntables as a means of isolating and extending the most rhythmic parts of popular songs — otherwise known as breaks — so that people can show off their moves. It’s a technique common in Jamaican dub music and Herc’s party-goers love it.

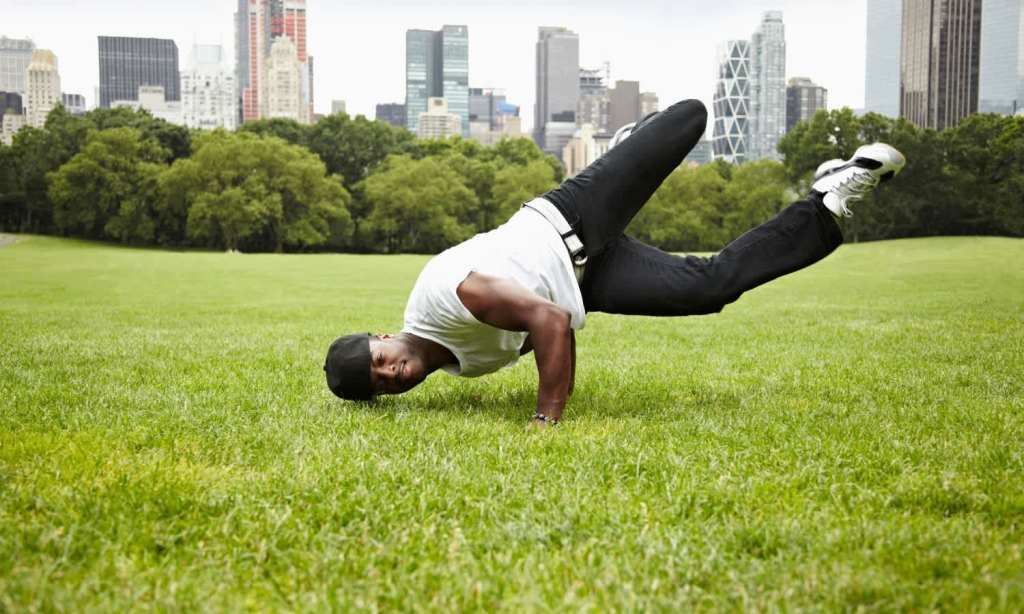

By the end of this momentous night, the course of mainstream music, urban culture and eventually sport will be indelibly altered. Tonight, what we know today as hip hop will be born and breakdancing will earn its name.

Almost half a century on from that balmy evening, the Olympics have announced that breakdancing, or breaking, will officially be included as a competitive sport at Paris 2024.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) shared the exciting news via Twitter with a post that read, “The @Paris2024 sports programme has been approved. It includes these main features: 100% gender equality. Four additional sports: Skateboarding, sport climbing, surfing and breaking. More youth-focused events. 10,500 athletes and 329 events #StrongerTogether”

The @Paris2024 sports programme has been approved. It includes these main features:

– 100% gender equality

– Four additional sports: Skateboarding, sport climbing, surfing and breaking

– More youth-focused events

– 10,500 athletes and 329 events#StrongerTogether— The Olympic Games (@Olympics) December 7, 2020

According to IOC president Thomas Bach, “We had a clear priority to introduce sports (that are) particularly popular among the younger generation and taking into consideration the urbanisation of sport”.

To make way for the newer sports, the IOC is cutting the number of weightlifting and boxing categories and rejected requests for other new events, such as mixed relay cross-country athletics and coastal rowing.

Shawn Tay, president of the World Dance Sport Federation (WDSF) responded eagerly to the news saying, “Today is a historic occasion not only for b-boys and b-girls but for all dancers around the world. The WDSF could not be prouder to have breaking included at Paris 2024… It was a true team effort to get to this moment and we will redouble our efforts in the lead-up to the Olympic Games to make sure the breaking competition at Paris 2024 will be unforgettable.”

British breakdancer Karam Singh was also thrilled by the announcement, adding, “It’s going to be great for breaking as it gives us more recognition as a sport. And for the Olympics, it will attract young people who may not follow some of the traditional sports.”

However, not everyone is over the moon at the inclusion, with some worrying that breaking will lose its authenticity by being judged on a global stage.

Considering the dance style goes hand in hand with a genre of music that evolved from a rebellion of sorts, it’s no surprise that there are concerns about breaking going mainstream.

If we look back at what is widely considered to be the birth of hip-hop on the aforementioned summers night in New York, we can see that hip-hop and, subsequently, rap were a form of self-expression during a turbulent time.

Under US President Nixon, a “war on drugs” raged on, obliterating Black communities as it did. Whether or not Nixon’s crusade was racially motivated or a well-meaning effort to save the American public from the devastating effects of illicit drugs, is a hotly debated topic but the effects of such a campaign affected people of colour in undeniable ways and continue to do so today.

Notably, 1973 was also the year the Justice Department sued Trump Management for discrimination due to the company’s practice of turning away potential black tenants from their many residential buildings. Named as defendants in the lawsuit were Fred Trump and his son — future president Donald. J. Trump.

The Trumps were hardly the only culprits propagating this type of prejudice, but rather just one example of it. Combine that with a conservative media who touted the negative narrative of “Black ghettos”, and a country that constantly invalidated the Black experience and you start to get an idea of the tapestry of injustice that made hip-hop and breakdancing so crucial.

In 2020, it has been abundantly clear that these issues, and countless others, are still just as relevant now as when the genre was originally formed to protest them so it seems only fitting that we make this significant step towards further inclusion at the 2024 Olympics.

And for those of you who still oppose this historic addition… what can I say? Them’s the breaks, kid.

Read more stories from The Latch and follow us on Facebook.