Trapped in a metal box, the size of a minivan, with four other passengers, at the bottom of the ocean. Oxygen is slowly getting depleted. The box is only big enough for one person to sit with their legs fully stretched, and you have no idea if help is on its way or not.

If this sounds like your own personal idea of Hell, then you’re probably not the kind of person who would ever find themselves in this situation.

While we now know that the five passengers on the OceanGate Titan submersible died instantly when the ship imploded, this was the nightmare scenario.

It was always a possibility that something would go wrong. Indeed, from what we now know about the safety record of the Titan, it was a likelihood. That didn’t stop the Titan‘s five crew from going.

The major search and rescue operation that captivated the world concluded on Friday morning with the revelation that debris from the Titan had been found on the ocean floor.

Throughout the search, the biggest question on everyone’s mind was, ‘Why on Earth would you do down there?’

The Titan had a tiny viewing hole, very limited facilities, and was operated by a PlayStation control. It was not exactly a joyride. The price of each ticket was also a quarter of a million US dollars.

Yet people undertake similarly extreme activities every day, knowing full well that they may not survive. We’ve all seen the photos of queues up Mount Everest or the people riding 20 metre waves at Nazaré in Portugal.

Dr Eric Brymer, of Southern Cross University, has spent his career examining why people put themselves so far out of their comfort zones. He told The Latch that there are fundamental psychological differences in the mentality of people who do things like this and people who sit safely at home.

“When we look at people that do this, we make the assumption that they’re the ones that are different,” Brymer said.

“But actually, if you look back in our history, the ones who are different are the ones who don’t do that”.

Human beings have always advanced as a species by being curious, resilient, and quick thinking in the face of danger.

Our modern society, Brymer argues, effectively keeps us from experiencing true, life-threatening danger and the adaptive advantages this cultivates. Therefore, the people who went on the Titan were living “what it means to be human.”

On board the Titan was 58-year-old British adventurer, Hamish Harding, 77-year-old former French Navy diver, Paul-Henry Nargeolet, and British-Pakistani father and son, Shahzada, 41, and Suleman Dawood, 19.

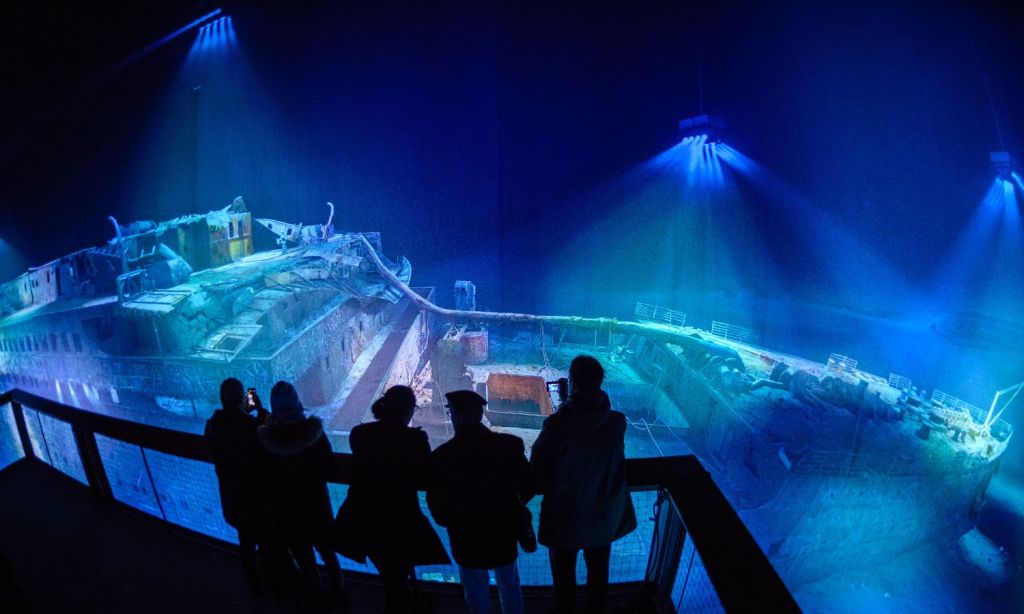

Leading the crew was Stockton Rush, a 61-year-old American engineer and founder of the company OceanGate. Since 2021, OceanGate has been offering wealthy tourists the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see what remains of the world’s most famous shipwreck.

For Brymer, it’s simplistic to categorise these people as simple ‘thrillseekers’ or ‘adrenaline junkies’ — you’d probably get a bigger adrenaline rush riding a rollercoaster than you would a slow-moving, mostly-dark submarine.

“I think that’s often what we miss. We sometimes think there’s just one reason why people become interested in doing these things and that it’s a personality thing,” Brymer said.

“For every single person on that boat, I’m sure there was a different reason as to why they wanted to go down there.”

With its historic significance, its watery isolation, and its lack of tourists, the Titanic makes an alluring mission for any adventurer. More people have walked on the surface of the moon than have seen the Titanic in person.

“Nobody is pretending these things aren’t dangerous,” Brymer said. But, he explained, there is “also something quite profound” that happens to people who do undertake these kinds of adventures.

“These things are transformational. [For the people who do them,] their experiences with others, their experience of the world, their connection to the natural world, their understanding of their own capacities and capabilities: All of those things change as a result of adventure.”

How Adventurers Respond to Danger

Just as there are numerous reasons why someone would be on the ship, there are also a range of possible reactions to something going wrong. For Brymer, his work would indicate that people like Nargeolet and Harding will likely be much better adapted to being in dangerous situation than the Dawoods.

The former, having undertaken a lifetime of dangerous activities, would have learned through experience the skills required to navigate potentially life-threatening situations. In fact, the below video shows Nargeolet speculating on what it would be like if their submarine became trapped underwater — something he seems relatively calm about.

The Dawoods, part of one of Pakistan’s richest families and friends to King Charles, did not have had the same level of exposure to danger.

“Some people just need to have enough money and have enough interest in the boat,” Brymer said. They could just be seeking bragging rights or the ultimate anecdote.

“The realization that they’re in this position where the potential outcome is death, that’s going to be a very unpleasant experience. It’ll be unpleasant for everybody, but for those people, there’s going to be almost a sense of disbelief that this can happen.”

Those of us on the surface are not too dissimilar to those who went on the submarine, expecting everything to be resolved, Brymer argues.

“We just take technology and all these safety measures for granted technology without really sitting down and examining what the implications are, what the reality is”.

Ever since it hit the ocean floor in 1912, people have been speculating about trying to reach the Titanic. Only recently has the technology to get down there become available to the public. Currently, there is a small but enthusiastic cohort of adventurers who have either been to the wreck or are itching to do so.

While this latest disaster may dissuade a few of the less-adventurous types, it won’t be the last time that someone pays a lot of money to see something few others will ever witness. According to Brymer, doing so is a fundamental part of human nature and perhaps the most ‘human’ we can ever be.

Related: A Viral Tweet Made Me Track How Often I Think About Titanic — Here, I Present the Results

Related: The Wreck of the Titanic Is Deep, Dark, and Dangerous: Here’s What Rescuers Are Up Against

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.