Welcome to The Great De-Vape, a three part series from The Latch‘s News and Culture Editor Jack Revell, drug policy nerd and author of the Drugs Wrap newsletter.

In part one, we look at the changes to vaping laws that are coming in this Friday, 1 October and why these changes are being made.

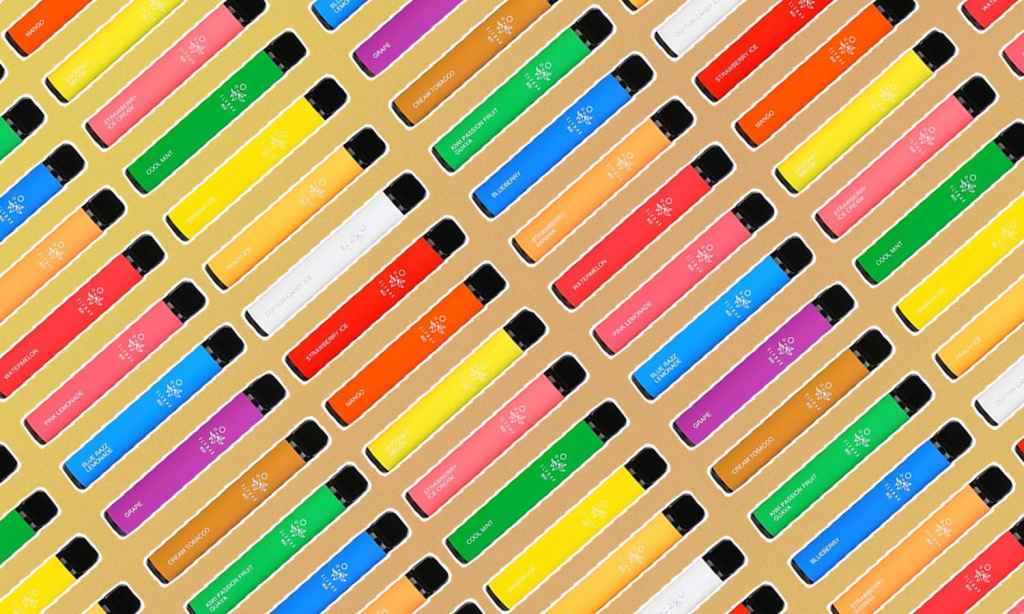

Walking around in any urban centre pre-lockdown, it would be impossible to miss the clouds of sugary vapour emanating from the mouths of seemingly anyone and everyone. Nor would it be possible to miss the build-up of those little metallic tubes, not much larger than a lipstick, that littered the pavements and pathways.

It appears that vaping has caught on in Australia in a massive way. While the ability to vapourise nicotine and its associated flavourings and chemicals has been around in a consumer sense for a little over a decade, it’s not until last year that Australia really seemed to make the switch — almost overnight.

Now, this is not data, but from my own observations, during the summer months of 2019 and 2020, the numbers of cigarettes being smoked on the streets and in the smoking areas of venues seemed to decline dramatically. Everyone in my social circles who smoke appeared to move from tobacco to vapour in a matter of weeks while the devices were suddenly available at every corner shop.

Again, this is little more than opinion, but there is good evidence to suggest that increased access to vaping probably has an impact on declining smoking rates. In the UK and the US, the popularity of the devices seem to correlate to declining smoking rates more than is explainable by any other factor.

While Australia has fewer people using vapes, and smoking rates have been steadily declining by a fraction of a percentage point each year, from what I’ve seen, it looks like these humble battery-powered devices have been able to do what so many aggressive anti-smoking campaigns couldn’t.

Cigarettes are out. Now, vaping is ‘cool’.

Which is a real shame because the Australian government, in its infinite wisdom, has chosen this Friday, 1 October, as the date when vaping will be effectively outlawed in our country.

This is not to say that vaping is good for you, or something that should be encouraged — far from it. The rise of vaping has come with its own set of problems, not least of which is the cocktail of chemicals of unknown health implications that the devices emit, along with the troubling, although likely overblown, rise in teenagers and young people with no prior history of smoking taking up the habit.

However, the upcoming ban will throw more than half a million people who use vapes into disarray as they scramble to attain prescriptions for their products. Some may return to smoking, others may quit nicotine altogether.

No one is really sure of the long term impacts of either this law change or the vapes themselves, but there are passionately held arguments on either side that have played out in Senate Committee hearings, lengthy online articles, and, of course, the No-Man’s land of social media, predominantly Twitter.

For better or worse, vaping will now be prescription-only in Australia. Here’s what we know.

Wait, They’re Banning Vaping?

From this Friday, if you want to vape, you’ll need a prescription.

Nicotine, except when contained in tobacco or nicotine replacement products like gum or patches, will now be a Schedule Four drug, illegal to own or use without permission from a GP.

In fairness, it’s kind of always been illegal. While the products have never been technically allowed to be sold, advertised, or used, they frequently and routinely are.

This is partly to do with the way they’re sold and partly to do with the way they’re classified. Vapes are both a medical intervention designed to get people off ciggies and a recreational device that give users a buzz.

Vapes sold in your local corner shop are often not advertised, nor are they supposed to contain nicotine, even though they frequently do and are purchased because of it. It’s kind of an open secret that has not really merited the attention of the authorities — until now.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration — Australia’s medicines regulatory body — claim that this change is simply to smooth over the rules that vary between governments and tighten the net on access.

In a statement to The Latch, the TGA stated that:

“By filling the present lacuna between Commonwealth and state and territory laws the decision will mean that, from 1 October, the Australian Border Force and the TGA are focussed on working together (as well as with the states and territories) to stop importation by individuals without a prescription.

“The ABF and the TGA have, since the beginning of the year, made this a planning priority in their broader ‘border’ work programme to provide for effective compliance and enforcement at the border”.

Won’t Somebody Please Think of the Children?

The real question behind all of this is why?

21,000 people a year die from smoking in Australia. There are more deaths from smoking than there are from alcohol, prescription drugs, plus illicit drugs, road crashes, and suicide, combined.

Over 520,000 people in Australia use vapes, figures that are probably under-counting the casual users and the recent uptick in usage, with relatively little complaint. These are people who would otherwise be smoking cigarettes, which we know are highly toxic, causing the deaths of two-thirds of lifetime users.

Vaping as a public menace or the source of public health concerns just isn’t there. Who was asking for this change and why?

One answer is health campaigners like the Lung Foundation Australia, who advocate an abstinence-based approach to putting anything other than air into your lungs.

Speaking to The Latch, Lung Foundation CEO Mark Brooke explained that “what we want to do is to say to people, ‘how do we work with you to enable you to get your healthy lungs in order?

“Not, ‘let’s substitute something which we know is bad for something which allegedly is less bad’. That’s not that that’s not good harm reduction.”

Brooke is keen to make the distinction between vaping as a recreational tool and as a means to get people off of cigarettes, something that he feels this ban will address by cutting out the former while still enabling the latter.

“The Lung Foundation is not, in any way, seeking to demonise or downplay how difficult it is to get off tobacco and nicotine based products,” he said.

“But you’ve also got this issue of what we’ve now classified as recreational vaping and the rise of young people who are never-smokers taking up vaping which is clearly not the right thing to do by your lungs”.

He says that over 800 parents, teachers, and school principals have reached out to his organisation seeking assistance to combat the rise of young people vaping and calling for a stronger regulatory framework.

This is a thematic issue that comes up again and again when discussing the topic. In my own experience, when I was a freelance journalist pitching stories about vaping last year, editors didn’t want to know about it. Throw young people into the mix and you’ve got yourself the makings of a moral panic and some hot headlines — unfortunately, the foundation of much of our national discourse around drug use.

The TGA appears to be spearheading their rationale for the decision with this exact argument. Their website cites a “significant increase in the use of nicotine vaping products by young people in Australia and in many other countries” as the primary reason for the ban.

They claim that, “Between 2015 and 2019, e-cigarette use by young people increased by 96 per cent in Australia,” figures that have no identifiable source.

They also state that “There is evidence that nicotine vaping products act as a ‘gateway’ to smoking in youth and exposure to nicotine in adolescents may have long-term consequences for brain development”.

Dr Alex Wodak, a board member of the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, has been combating social stigma and the resultant policy failures around drug use since the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

He describes the “teen-vaping epidemic” as a “myth” based on “very rubbery statistics”.

“People get counted in a ‘teen vaping epidemic’ if they’ve vaped once in the last 30 days. Well, that’s not a vaping epidemic,” he said.

“Vaping is common amongst people who are already smokers. Sustained vaping is very uncommon in people who haven’t smoked yet”.

The figures bear this out. According to the latest National Drug Strategy Household Survey, only 1.8% of 14-17 year olds had vaped once or more in the last 12 months. Of the overall population, only 1.3% of non-smokers had ever vaped.

“How can vaping be a gateway to smoking when the smoking rates are going down,” Wodak adds, “particularly among the youth?”.

While he doesn’t go in for speculation over the motives of others – he’s much more interested in the health outcomes — Dr Colin Mendelsohn, Founding Chairman of the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, does expand on what he sees as the politics of the situation.

“I think primarily it’s because Greg Hunt wants to ban vaping,” he said, calling out the Federal Health Minister.

“He’s always wanted to ban nicotine or to restrict it as much as possible,” Mendelsohn explains, because he’s “got a personal issue about it”.

“In this debate, it’s much more than about the evidence, it’s all about ideology; ‘we can’t have people using drugs’. There’s a moral element, there’s a very puritanical element, there’s an abstinence-only debate issue, there’s the whole ‘what about the kids?’ thing”.

There is also quite possibly one of the most important factors too: the financial issue.

“There the $17 billion in tax,” Mendelsohn said.

“There is so much money involved in tobacco. There must be pressure from the treasury. It’s the fourth biggest tax in Australia, The fourth biggest. That’s more than petrol. I think financial factors are a major factor.”

The argument that the government would seek to restrict smokers from switching to a less harmful product because it is so clearly effective in doing so is far and away the most cynical take, however it is a view held by a lot of the vaping community.

“We have the highest cigarette prices in the world. A lot of smokers see that as just a cynical tax grab by greedy government because they use very little of that money to help smokers quit,” Mendelsohn said.

It’s not used for that, it just goes into consolidated revenue and it’s not used for people who need it most”.

The story continues in part two where we look at just how dangerous vaping is for you.

Part three examines what the impact of the new laws will be for smokers, vapers, and society.

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.