The Queensland Government has suspended its own human rights act in order to create laws designed to make it easier to punish children as young as ten. For the second time. This year.

On Wednesday, QLD Police Minister Mark Ryan introduced a 57-page amendment to an unrelated 48-page Bill that allows the government to imprison children in prisons and watch houses for adults, indefinitely. The amendment was added at 3:30pm and the House was given just half an hour to debate it.

Because the amendments were tacked onto an existing Bill about child protection, they will not have to go through Parliamentary Committee for review. The amendments also include significant changes that decriminalise public drunkenness and begging, while also protecting sex workers from police surveillance.

The rushed changes have prompted an outpouring of criticism, with one MP calling it the “biggest affront to democracy in Queensland’s history”.

Greens MP, Michael Berkman, attacked the Government for the short notice.

“To call this disgraceful is an understatement,” he said. “It is an absolute dog act for the government to introduce amendments like this with no prior warning.”

BREAKING: I've just seen one of the most disgraceful acts from Qld Labor since I was elected.

At 3:30pm, they moved 57 pages of amendments to an unrelated bill w 30 mins for debate.

They suspend the Human Rights Act to allow children to be kept in watch houses & adult prisons.

— Michael Berkman (@mcberkman) August 23, 2023

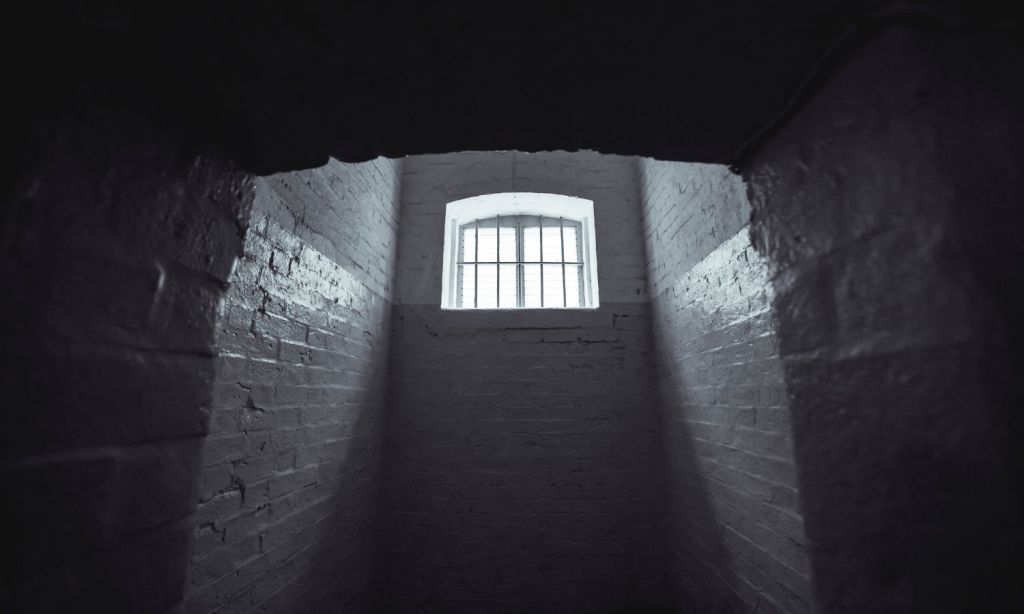

The laws will allow the government to keep children in “what are essentially concrete boxes,” said QLD’s Human Rights Commissioner, Scott McDougall.

“There are farm animals with better legal protections in Queensland than children.”

The move sparked protest outside Queensland Parliament yesterday organised by the women and girls rights group, Sisters Inside. Indigenous rights groups, like Change the Record, have also come out in opposition to the proposed laws as they argue it will have a disproportionate impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island children.

Queensland Labor's appalling decision to suspend the Human Rights Act means children as young as 10 can be held in a watch house or adult prison indefinitely.

Thank you to Sisters Inside for organising the snap protest & to everyone who came along. pic.twitter.com/puX4eBmZoR

— Queensland Greens (@QldGreens) August 25, 2023

“Queensland’s new watch house laws will have a devastating effect on Aboriginal communities,” Change the Record’s National Director, Maggie Munn, told The Latch.

“Aboriginal children are incarcerated on mass in the state and across Australia due to racial profiling, over-policing, and a complete and utter failure on behalf of governments to address the systemic disadvantage, discrimination and racism our people face,” they said.

The Queensland Government have defended the changes, describing them as “business as usual” and part of their continued “tough on crime” stance. Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk told 7 News that it’s the Government’s job to “keep the public safe.”

“The public have been pretty loud and clear that they want the community protected, and this is just one means,” the Premier said. “It’s not our desired outcome.”

Palaszczuk noted that the law “formalises” what the state has been doing for the past three decades and that Queensland is not the only jurisdiction to do this.

The latest move, however, has been interpreted by Indigenous activists as just the latest in a legacy of failures the Queensland state has towards Indigenous people.

Why Is the Queensland Government Doing This?

It appears that the Government has been caught on the back foot here. On some days, there are more than 100 children in adult watch houses — a building used by police to keep people under temporary arrest when they are suspected of having committed a crime — throughout the state. As it turns out, many of those may have been kept illegally.

At the start of the month, the Queensland Supreme Court ordered the urgent transfer of three children from police watch houses after finding that the Government had no legal basis to detain them.

This is Qld Labor’s media release on their last-minute amendments to override the Human Rights Act so that children as young as 10 can be held in adult police watch houses and prisons.

I don’t even have words to describe how disgusting it is to call this “business as usual”. pic.twitter.com/l0lQkx8NAG

— Michael Berkman (@mcberkman) August 23, 2023

This was after a Cairns-based organisation, Youth Empowered Towards Independence, lodged a case to have several children transferred to youth detention centres. The State’s Solicitor General, Gim Del Villar, told the court that he couldn’t produce specific orders that allowed the children to be held in police custody.

Guardian Australia‘s Queensland State Reporter, Eden Gillespie, who has been reporting on the story, has written that Del Villar later informed the Youth Justice Minister that Queensland may have been illegally detaining young people for years without realising it. Over the past 30 years, the Government’s interpretation of the Youth Justice Act was “likely incorrect.”

The Government panicked, rushing to introduce legislation this week that legalised their past practices. Youth Justice Minister, Di Farmer, said that without doing so, any further court challenges would make it “highly likely that every single young person would have been transferred immediately from the watch house to the youth detention centre”.

What’s It Like in a Watch House?

Queensland has justified the practice of holding children in police watch houses — sometimes for as long as 40 days — by saying that youth detention centres are too full to transfer them to. This is despite the fact that the Queensland police’s operational manual says that children should only be detained in a watch house for more than one night in “extraordinary circumstances.”

Being at capacity has meant police watch houses have become default holding cells. The conditions are often solitary, bare, and dark, having been described as “traumatic.” In a report published by the Queensland Family and Child Commission last year, teenagers shared their experiences of being held in watch houses for over a month.

“If you come on weekends, they don’t give you showers, they make you wait until Monday,” said one 17-year-old boy in the report.

“If you’re locked in on Friday, you’ve got to stay in there in your same clothes. And don’t have a shower until Monday… and they make you drink [from] a tap on top of the toilet …”

Others described being unable to sleep because of the noise in the cells and the lack of cushions on the block beds.

One Queensland magistrate granted bail to a 15-year-old girl in Mount Isa in February over concerns she would be held in “harsh” watch house conditions for an extended period of time.

The children being held “are usually open to the sights and sounds of the watch house,” the magistrate said.

“It suffices to say that conditions in watch houses are harsh and that adult detainees are often drunk, abusive, psychotic or suicidal.”

A Queensland whistleblower earlier this year reported seeing illegal strip-searching of children, staff wrapping towels around prisoner’s heads to avoid spit hood restrictions, and even a young girl being put in a cell with adult men. More often than not, these young people have a childhood of trauma compounded by state action.

“The small children who will experience the brunt of new watch house laws have experienced trauma in their short lives — if data can tell us anything, nine out of ten of them have a neurological impairment, 60% of them are First Nations and three in 5 have been victims of family violence,” Munn told The Latch.

“They are in need of care and support and Queensland instead is taking them from their loved ones and locking them in cold dark watch houses with adults for indefinite periods of time”.

“These are no places for children and expose them to significant harm and trauma”.

What Does Human Rights Law Say?

Australia has long been criticised by human rights organisations for the “widespread” locking up of children. The Australian Human Rights Commission has stated that both domestic and international law is clear when it comes to detaining children and that it must only be a “measure of last resort.” The proposed changes to Queensland law, as well as the historical actions of the state, are in direct violation of these principles.

“Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, a child should only be detained as a last resort, and for the shortest appropriate period of time,” National Children’s Commissioner, Anne Hollonds, said in response to the latest news.

“They must also be segregated from all detained adults. Queensland’s Human Rights Act specifies that an accused child who is detained, or a child detained without charge, must be segregated from all detained adults”.

The issue with international human rights law is that it is very hard to enforce. Australia became a signatory of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990, but has subsequently been criticised multiple times by the UN for failing to uphold it.

In 2021, Australia rejected UN calls to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14, a criticism levelled at the country by over 30 member states. In response, the UN can do, well, not a hell of a lot — except continue to make calls to Australia to fall in line with international standards.

In 2019, Queensland introduced its own Human Rights Act which offers legal protection over 23 rights it considers fundamental. These include the right to protection from “cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment,” the right to “humane treatment when deprived of liberty,” and the rights of children in the criminal process.

The Act also states that Parliament must consider human rights when proposing and scrutinising new laws. However, Queensland has appeared quite cavalier in regard to the Human Rights Act. In February, critics attacked the Government for making it a criminal offence for a child to breach bail orders.

Amnesty International Australia said at the time that the Queensland Government’s decision was “in blatant contravention of children’s rights” and highlights how inadequate human rights protections are in Australia as the only liberal democracy in the world without a national human rights protection, such as a constitutional bill of rights.

Effectively, without such a solid legal device, Federal and State and Territory Governments can decide how they wish to interpret their own human rights legislation.

“I don’t think it’s okay in a society that claims to value human rights,” McDougall said of the recent change on ABC Radio Brisbane.

“[The Government] introduced an act in 2019 that set out the 23 rights that Parliament said would now be protected in Queensland. It also said that human rights would only be overridden in cases of exceptional circumstances and in the act it says a war or a public emergency”.

McDougall went on to say that “expert after expert” has explained that community safety is not improved by locking up children.

Proportionally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are the most incarcerated people on the planet.

Related: A Complete List of the Age at Which Australia Is Comfortable Locking Up Children

Related: Three Decades After the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, What’s Changed?

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.