The government has released a massive, 1000-page report warning that our pay could drop by 40% while we work an extra two hours a week unless we increase productivity in Australia.

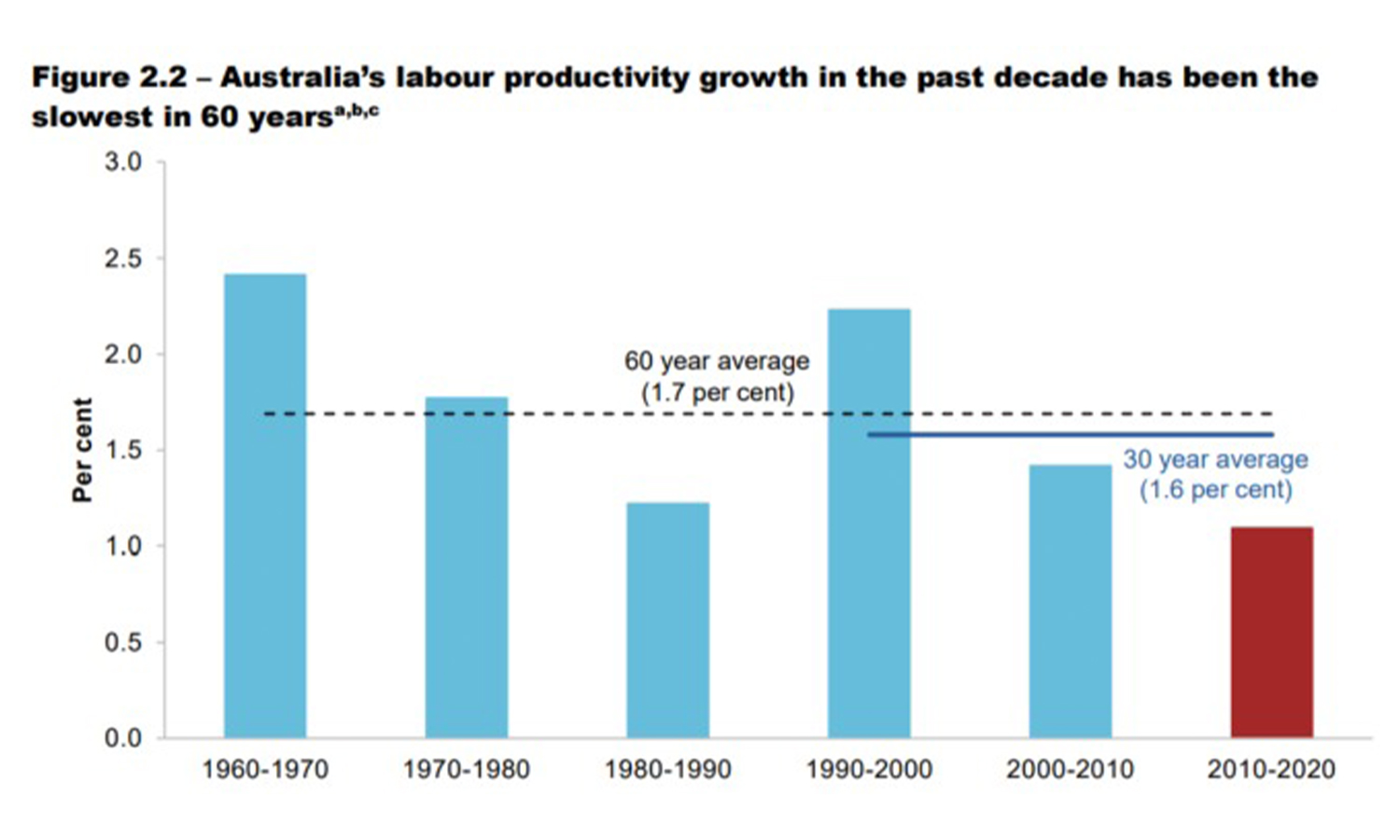

The Productivity Commission report found that national productivity has increased by just 1.1% per year over the past half a decade. This is the lowest level it’s been 60 years.

“Our report shows how productivity policy is central to a modern economy,” Productivity Commission chair Michael Brennan said.

“There is no easy answer, but we need to address this challenge to secure Australia’s future prosperity.”

In a speech on Thursday, ahead of the report’s release, Treasurer Jim Chalmers described our productivity performance as “woeful” and the past decade as “wasted.”

“On every traditional measure of productivity, Australia has been flatlining. Australia has a productivity problem,” Chalmers said.

The report clocks in at nine volumes and comes with 71 recommendations. Although it wasn’t due out until after the budget, Chalmers has said that he has released it early so that we can understand why he’s probably not going to sprinkle us with cost-of-living assistance in May.

That’s a heap of detail, so we’ve pulled out the juiciest and most important bits of info and distilled them down to their essential components for you here.

What is Productivity?

In basic terms, productivity is the measurement of the value of stuff that can be created by people over time. For example, if someone spends an hour making a hat, and that hat can be sold for $20, labour productivity would be $20 per hour.

Productivity typically increases over time as more efficient means of creating things are developed. In 1901, it would have taken half an hour of work to afford a litre of milk. In 2019, that was down to an average of 2.2 minutes since milk became much cheaper and easier to produce over that time.

Rising productivity generally leads to an overall rising standard of living. With productivity flatlining, the Treasurer is worried that our living standards could decline in the long term and our wages may drop.

Productivity is Dropping

Over the past fifty years, Australia has dropped 10 places in global productivity rankings, falling from 6th to 16th. Our productivity is now lower than America’s by 22%. If productivity had increased in line with our 60-year average, average wages would have been $4,600 higher by 2020.

However, productivity really fell off a cliff in the past decade and is now just over half of what it was in the 90s.

Why is Productivity Dropping?

Australia is not the only country with a productivity issue. Many developed nations have been experiencing productivity slow-downs over the past few decades.

There are a number of theories as to why. Some economists think that we’ve gone through the mass innovation gains of technology, and all the easy wins have been won. Others say that developed economies are more service-oriented, where productivity can’t really improve. You can only make so many coffees per hour, or grade so many papers, for example.

This appears to be the key issue with Australia, as the report shows that almost 90% of us now work in service industries like education, healthcare, hospitality, retail and finance.

“It has traditionally been difficult to lift productivity in these sectors,” Brennan has said.

There are also demand issues. Households have been buying less stuff since the 2008 financial crash. The pandemic didn’t help this either, and now the cost of living crisis is seeing people spending less. Because of that, there’s less incentive for people to make things and workshop new, innovative ways of doing it.

Higher regulation, more automation, and the lack of competition in major industries like retail, banking, technology and communications, have also all been blamed. What’s more, some economists say that infinite growth is basically just a fantasy, and that an economy based on increasing productivity forever is going to fail eventually.

What Are We Going to Do About It?

The report’s 71 recommendations focus on five ‘key themes’: building an adaptable workforce; harnessing data, digital technology and diffusion; creating a more dynamic and competitive economy; efficiently delivering government services; and securing net zero emissions at the least cost. They’re talking about basically updating the whole economic framework.

These recommendations mainly focus on improving education, targeting migration so as to attract people with plans to start businesses here, and improving access to digital infrastructure. A lot of it is really saying ‘do stuff better’ by cutting red tape, minimising government overlap, and generally raising standards to make it easier for people to do business. This shouldn’t, however, come at the cost of quality, the report emphasises.

Chalmers has been talking about productivity since he took office. In his mind, increasing productivity is the secret to driving higher wages and greater prosperity — even if increased productivity hasn’t been linked to higher wages for decades.

The simplistic view of the productivity figures would say that Australian workers (and Western workers more broadly) are simply lazy, distracted, and don’t want to work. But productivity isn’t just a measure of labour hours; it’s also a measure of how effectively we use our money.

In terms of input hours, labour productivity has never been higher, but capital productivity, the value created by investment, continues to decline. This is where big gains can be made. Mining is one area where productivity has fallen, but it’s also a major attraction for investment, meaning that better management of resources and time for those investments to pay off are needed.

But there isn’t one easy fix to this structural issue. Arguments over how to increase productivity have been raging for decades, with many pointing to better management, increased investment in new technologies, the training up of workers to adapt to new industries, and the starting of new businesses.

The Reserve Bank, having held interest rates at historic lows for many years, has long been imploring governments to implement policies that will boost investment and support innovation. But besides mining, there has been a major drop off in investment over the past three decades.

The Treasurer has already said that the government won’t be adopting all of the 71 recommendations from the Productivity Commission report, but they will look to “invest in people,” fix the energy markets, and ensure technology is being adopted appropriately.

Likely, productivity gains are not going to be made by making workers perform longer hours in inefficient roles. It’s a ‘work smarter, not harder’ mentality that the Treasurer is keen to adopt. Otherwise, we’ll continue to work harder for less and less return.

Related: Has Silicon Valley Bank Triggered Another Global Financial Crisis?

Related: The RBA Puts the Boot in With 10th Interest Rate Rise

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.