Electronic musicians have been impersonating robots forever. Now, robots are trying to impersonate DJs.

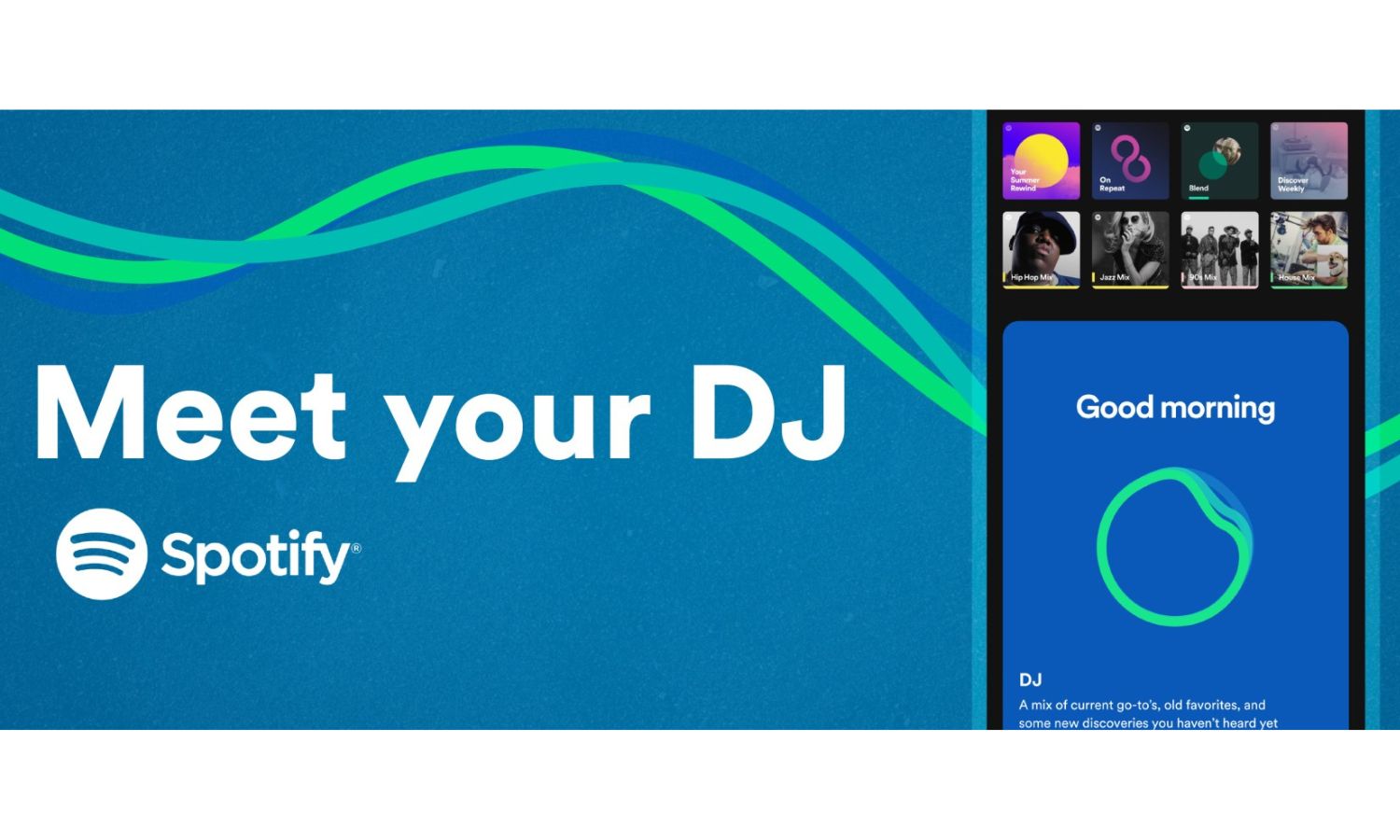

Spotify has released a new AI DJ feature in Australia. After testing the service in the US and the UK, the music streaming platform has opened it up to Australia, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Spotify describes the DJ feature as a “personalised AI guide that knows you and your music taste so well it can choose what to play for you.”

“DJ provides a new and different way for fans and artists to connect,” the company writes in press materials.

Users in Australia will, from today, be able to open their Spotify apps and select ‘DJ’ under the ‘Made for You’ section in their home page. Once playing, the AI service will play songs it believes the user likes, interspersed with AI-generated commentary every few songs.

“Hey, what’s going on [name], it’s really great to be here with you,” the AI voice says when you play the feature.

“I’m going to be your own personal AI DJ on Spotify. Yeah I’m an AI, but listen, I don’t set timers, I don’t switch on your lights. I’m all about the music, your music,” the AI says, making its elevator pitch.

The AI voice is based on Spotify’s Head of Cultural Partnerships, Xavier “X” Jernigan. Spotify has previously said that using a human-sounding voice “is key for users to foster a deeper connection with DJ.”

In truth, it’s not clear how much ‘AI’ — the buzziest of contemporary buzzwords — is being used here. In 2022, Spotify acquired London-based tech start-up Sonantic, the AI voice company that re-created Val Kilmer’s voice for Top Gun: Maverick.

“This integration will enable us to engage users in a new and even more personalised way,” Ziad Sultan, Spotify’s Vice President of Personalisation said at the time of the acquisition.

It’s Sonantic’s technology that the company have used to create the human-like realism of the DJ voice. However, the words spoken are still a mix of human input and generative AI. This is a type of artificial intelligence that can create text or images based on learning the patterns and structure of training data.

“To help arm DJ with knowledge and expertise, we created a Writers’ Room with music experts, culture experts, data curators, scriptwriters, and generative AI,” Head of Global Hits, J.J. Italiano, has said of DJ.

Primarily, what the new feature is doing is adding a Siri-like layer of voice interaction to Spotify’s already vast wealth of data it has stored on its users. Much like the popular song radio functions and ‘for you’ playlists that Spotify creates for its users, DJ simply feeds them an informed music playlist, smoothed over by radio DJ-esque chat.

The DJ voice often drops in the name of the artist of the next track in the playlist with a phrase such as “I think you’re going to like this one by [artist name].” Therefore, the levels of ‘AI’ in use here are likely to be fairly minimal and, as Spotify has said, still fairly hands-on.

However, while Spotify’s latest move is not yet reason to believe we’ll all be rocking out to AI selectors any time soon, it’s another step toward an automated future that will have serious implications for the music industry.

There’s Something About Us

DJs get a lot of flack. Social media often loves to call out those barely-doing-anything artists who stand behind the decks and let the machinery do all the work. But the role of a DJ is a much more complex and nuanced one than you might first think — and far more open to AI automation.

The Latch reached out to a number of DJs to gauge their thoughts on the latest development. Overall, it didn’t seem that many were much concerned about this specific iteration of AI-assisted song selection.

“DJing is reading an environment and the multitude of people in it and building a feeling or emotion with those people,” Toby Wallace, a Sydney-based DJ who plays under the name Tobeleron3, said.

“Unless AI can read a room full of people, the lighting, ambience and energy it is incapable of doing the basics of a DJ”.

However, DJ as a crowd-response music selector is not their only role and there were concerns raised about the broader trajectory of the technology.

“DJing, and music performance in general, is such a broad thing and means different things to different people,” David Joseph, a Sydney-based DJ who plays under the name Jejemon, told The Latch.

Having played everything from illegal warehouse raves to weddings, he said the role of the DJ is highly context-dependent and that some aspects are more vulnerable to automation than others.

“At a corporate event, you are just kind of a combination of eye candy and a prestige item,” he said. “In the case of DJing for a wedding or a birthday party, more often than not, you are a glorified Spotify playlist.”

DJs are booked and hired for events where the organiser wants a live human to be in charge of music selection. Responsibility is turned over to them and they trade on their reputation as a music selector. In that capacity, DJs bring a wealth of musical knowledge and an extensive catalogue of tracks, with much of the role relying on being able to read the vibe of a venue.

However, none of these are things that AI won’t eventually be able to do — if it can’t already. Indeed, there is some suggestion that people wouldn’t notice or miss a human standing in the corner of a bar selecting songs if they weren’t there.

When playing bar gigs, Newcastle-based DJ and producer Brendan Zacharias, who plays under Assembler Code, said that “half the time people don’t even know that there’s a DJ there.”

“But you’re a vibe curator. There is a human watching the scene, seeing someone get up on the dance floor, and making a decision in the moment of what song comes next. It’s a highly tailored job,” he said.

That said, Zacharias can imagine a future in which a camera and a microphone in a bar could be fed into an algorithm that is trained to detect ‘vibe’ and respond with music accordingly. With the addition of an infinite catalogue of music and the use of automated track-synching technology that DJs already employ, AI could be a serious threat to DJs if all the pieces were put together.

“But why would someone go to such lengths to do that?,” Zacharias asks.

The answer is, as with everything, money. If a venue spends, say, $100,000 each year booking background DJs for vibe curation, would they really not want to cut costs if the same could be achieved for a few thousand in technology leased from an AI firm? In that sense, it’s not just AI that creatives are up against but the relentless logic of capitalism.

Human After All

Beyond the ‘vibe-curation’ role that DJs fulfil, there is also the human talent element. People will pay big money to see big-name DJs on the basis that they are getting an experience they can’t get elsewhere. It’s an expenditure based on the unique nature of the talents of that human artist which AI cannot replicate.

Whether AI could start to impede the positions available to musicians is already evident. In 2012, technology was used to ‘resurrect’ rapper Tupac Shakur to play in front of a sold-out crowd at Coachella. Last year, ABBA was able to use similar smoke and mirrors to digitally perform as they were at the height of their career. There is a burgeoning industry combining AI with ‘holograms’ to ensure artists keep playing — and raking in money for their labels — forever.

While those artists are alive, however, AI poses different risks. CDs didn’t kill vinyl, nor did mp3s and streaming. But they did radically change the environment in which vinyl was bought and played. Zacharias sees the comparison to artisan produce as a potential future for both music production and DJs.

“It’s sort of taking up the bottom end of the market, but there’s always going to be the top end,” he said.

Zacharias, who has played DJ sets across Europe, said that it’s already hard to justify spending time creating music and is concerned that AI could start making that more difficult.

“It’s a very privileged position to be able to spend three hours farting around with a random synthesiser and come up with a track because I can justify this work only after the fact, when it starts to get me gigs or I can sell it,” he said.

“So to write it on a speculative basis is really difficult to do. And if AI could write Assembler Code tracks better than I can because it’s scanned my entire back catalogue, and it can do 20 in an hour, well, I can’t compete with that”.

Electronic musicians are, by nature, innovators. But Zacharias has said that there ought to be protections in place over how AI is used to protect jobs in the creative industries.

“I’m not against AI, because I think progress is really important and we should be pushing things forward, but we just need to make sure that it’s regulated so it doesn’t become just a top 1% situation,” he said.

Ironically, DJs are in themselves already a representation of technology disrupting live music. Before you had a single DJ with the ability to play hundreds of songs in a night, you had live bands with a limited catalogue. They were also much more expensive to hire.

Technologic

It might be currently unthinkable that AI could replace DJs — people will always want to see talented musicians perform live for them. However, the idea of the superstar DJ who holds the crowd’s focus is a relatively new one.

“If you think about the origins of DJing, you had people like Frankie Knuckles playing in the 80s and 90s in clubs in New York and Chicago — no one saw them,” Joseph said.

“They were in a little booth, hidden away. No one actually wanted to see the DJ, that wasn’t the point”.

Therefore, it’s not beyond possibility that DJing could once again become an anonymous art form — only the selector isn’t in the room, they’re up in the cloud. Each bar or club could pay to have an algorithm tailored to its own particular vibe with an AI musician spinning the tracks.

If that were to happen, even slowly, the number of gigs available to early-career DJs would be placed at greater risk. Joseph argues that AI risks further entrenching class inequalities in the music industry.

“There are fewer and fewer working-class creatives now. AI is just the logical conclusion of already an uneven power dynamic,” he said.

“A lot of things in the creative arena have come from working-class environments. So by making it even harder to allow this kind of space to express itself and flourish, I think a lot may be lost in that”.

Robot Rock

Zacharias is confident that the essential humanity of a piece of creative work is something that a computer will never be able to replicate. It’s the argument a lot of creatives in their respective fields rely on — never mind the fact that a robot has already been proven to be able to create a more ’emotional’ and ‘human-like’ piece of classical music than top-end composers.

Other artists have read the writing on the wall and embraced the automated future. Earlier this year, Grimes instructed fans to take her vocals and use AI to create new songs. She later described one of the produced tracks as a “masterpiece.”

With respect to DJing, Japanese artist Nao Tokui has been playing ‘back-to-back’ sets with AI selecting every other track since 2016.

Karlovy Lazne, a nightclub in Prague, debuted a robot built by KUKA Robotics that DJs by itself in 2018. The giant robotic arm can select and play CDs and appears to be able to mix tracks together.

However, reports at the time suggest that club-goers weren’t overly impressed with the ‘inhuman’ nature of the song selection.

Give Life Back to Music

If the market is ultimately what will decide the future of DJs and creatives in general, then some form of regulation is likely going to be necessary. That’s a big question, in a global market, is how that is policed and enforced.

Over the weekend, a brand new song called “Everybody But You” caught the ire of record executives as it featured the remarkably human vocals of legendary Beatle, John Lennon — who has been dead for over 40 years.

The track was released by a relatively unknown artist called Kid Klava on TikTok back in June, who said it took them very little time at all to create.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pGk1nfStHCM&ab_channel=KidKlava

One music executive, responding to the track, said that the use of AI in this way “seems entirely wrong and open to huge abuse.”

“The use of some of the greatest ever artists to artificially perform and promote songs is a nightmare for us,” they said.

Universal, the world’s biggest record label has previously argued that copyright laws be applied to data used to train AI machine learning algorithms. They have been targeting AI videos posted online using their artist’s vocals and are currently working on licensing agreements with Google.

“Why are we getting AI to take away the most human things like writing poetry and creating images and paintings and music?,” Zacharias asked.

“We should be getting AI to do the time-consuming stuff that we want to free up. It’s kind of a utopian idea but, if AI does start taking people’s jobs, it’d be great if we somehow fed them some of the funds. I know that’d be really hard to do,” he said.

“I think that it should always be a tool which enhances what a human can already do, as opposed to something which replaces. We’ve just got to make sure we’re not losing the culture in all of this”.

Related: Tens of Thousands of Men Are Dating AI Girlfriends — But It Might Not Be a Bad Thing

Related: Hollywood on Pause: The SAG Strike Explained

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.